The rules regarding realization become less strict as the number of real parts increases. The two outer parts must always maintain a harmonic relationship which follows the purity of realization as much as possible. But the harmonic relationship between the inner parts, and the relationship between an outer part with an inner part, are much freer in harmony with three and four parts.

A direct motion can result in a perfect fifth or octave, even a second or a seventh.

Two consecutive perfect fifths and two unisons or two octaves are always forbidden by similar motion. But two perfect fifths or two octaves are allowed by opposite motion.

Crossing of the inner parts can be frequent.

The rules regarding notes to be doubled remain basically the same as in four part harmony. The third is always doubled the least. Thus, a single third may be enough for a tripled root and doubled fifth. However, these rules become less strict because of the number of parts, and either because of the melodic demands of the parts or the space left between the outer parts. These reasons often cause unisons.

It is necessary to avoid doubling notes with a constrained resolution. However, some authors offer examples in which a dissonant note or leading tone is doubled. But in these cases, on of the doubled parts makes an irregular resolution.

Regarding the suppression of certain notes in chords, its clear the more parts there are, the fewer reasons for suppression, and its applicable only in certain circumstances.

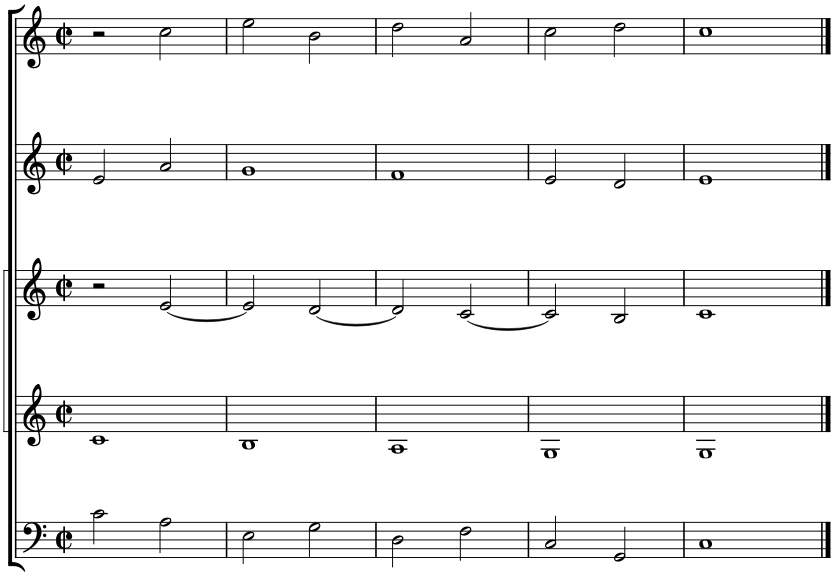

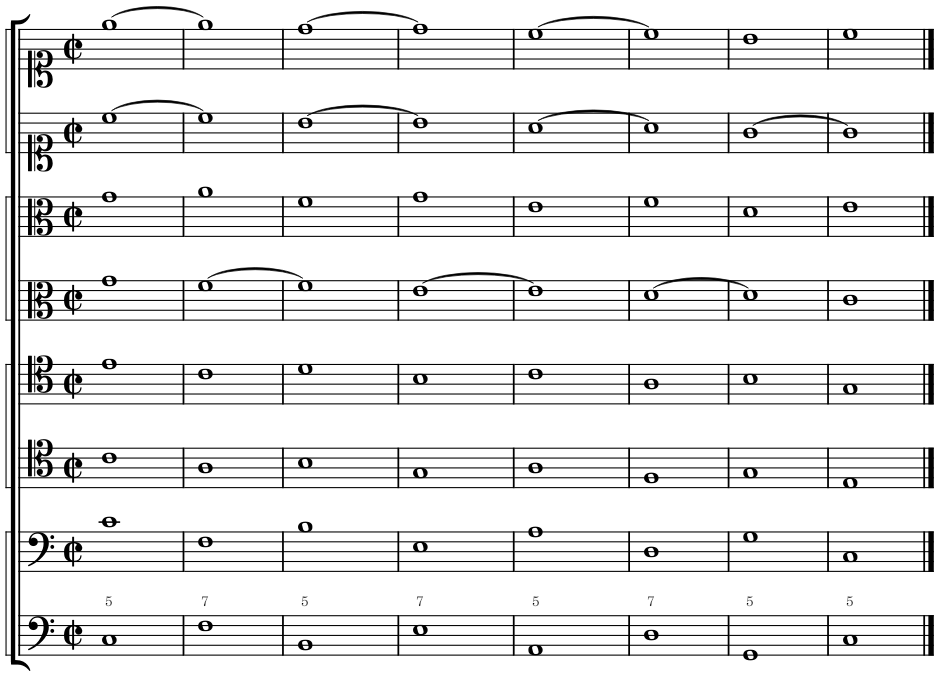

Various examples of harmonic steps in more than four parts

IN FIVE PARTS

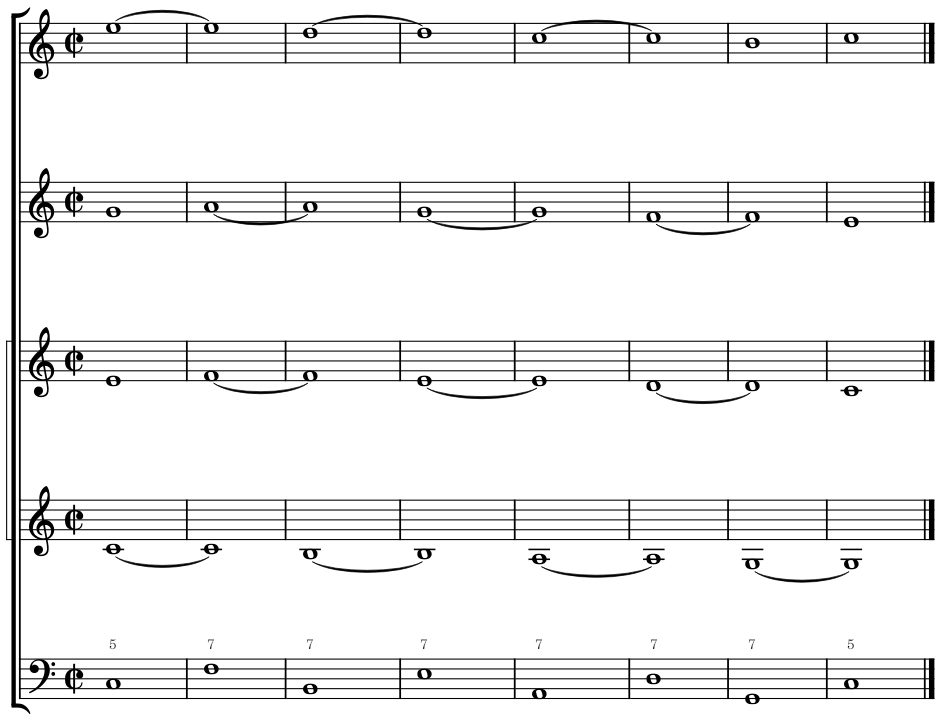

IN FIVE PARTS

IN FIVE PARTS (*)

(*) See the same example in four parts, CH. 11.0 No. 3b.

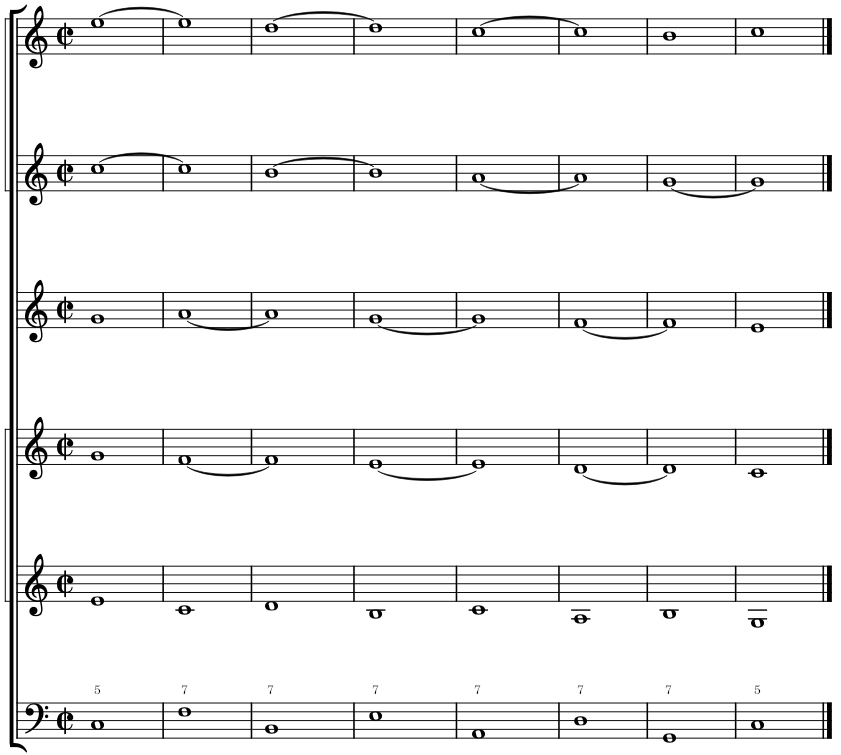

IN FIVE PARTS

IN FIVE PARTS

IN SIX PARTS

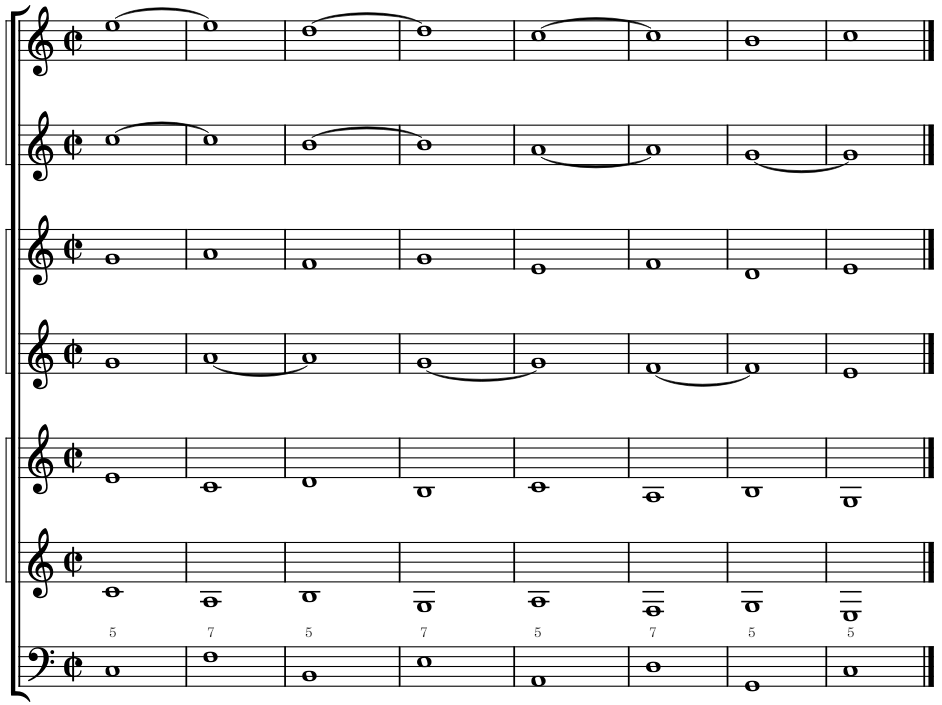

IN SEVEN PARTS

IN EIGHT PARTS

Its not uncommon to find, from masters before the 18th century, composition of five and up to eight parts. Modern music (late 1800s) contains few full pieces written entirely in more than four or five real parts.

Four part harmony is the most common of all. Its also the most perfect, as it provides enough parts to give most chords their fullness, yet isn’t complex enough to hinder the composer from giving each part melodic interest, nor prevent the listener from grasping the different melodic designs. But the more parts are used, the less free and less distinct their melodies become. More parts are also the source of confusion.

For these reasons, music is usually only written in four or five real parts when composing with a large number of voices or instruments, sometimes to complete certain chords only possible by separating the parts, sometimes to reinforce some passages by double the predominant part in octaves or unisons. A greater number of real parts is used in passages which lend themselves to this kind of realization.

However, when the student know the skill of composition to be developed from the Second Book (Parts III and IV), it will be essential they practice writing to a large number of parts, mainly five and six parts.