Tonality is the result of the relationships, either melodic or harmonic, of several sounds.

These relationships are necessarily subject to laws. Sometimes natural laws consistent with the divisions given by a resonating body that’s vibrating, And sometimes conventional laws dictated by habits resulting from our musical education.

Regardless, a simple melodic progression of several notes is enough for the musical sense to instinctively seek a relation of these notes to a principle note called the tonic. This set of notes which contribute to the tonal effect constructs a scale, and this scale is always the name of its first degree, its tonic.

Any melodic or harmonic sequence that doesn’t cause a tonal sensation forms an incoherent arrangement of notes rejected by the ear and musical sense. Thus, tonality is the first and most important condition of modern musical art.

While the scale is the most complete and irrefutable formula of tonality, the tonal impression can be established without all notes of the scale, since certain melodies only containing three different notes can establish the tone.

Finally, the need for tonality is so compelling that a single isolated sound is accepted as the tonic by any ear, even with the most basic musical abilities. Unless an earlier impression or habit suggests otherwise.

Reflecting on all that’s been said on tonality, we must conclude most of the conditions that contribute to establishing the tone also establishes the mode. Thus, in any case, the tone necessarily tied to one of the modes.

However, the minor mode is determines with the help of the 3rd and 6th degree. Example:

Any melody without the 3rd nor 6th degree is accepted by the ear as the major mode. Example:

This example, unless there is a previous impression (like the example before), or predisposing cause, produces the sensation of A major not A minor. This is because the major mode is natural and perfect, the musical sense doesn’t need to be constrained to perceive it. But the minor mode, being conventional and imperfect, requires clear and absolute conditions to be perceived.

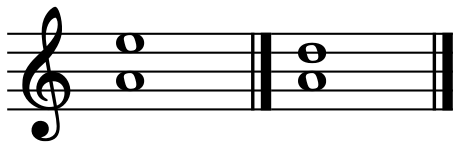

For the same reason, certain harmonic intervals, deprived of the notes that determine the mode, always causes the impression of the major mode. Example:

The same is true for an isolated note. The musical sense necessarily lends itself to the major third, this interval being one of the harmonic sounds of a resonant body in vibration.

The word key is often synonymous with tonality. However, “tonality” has a general and abstract sense, as the tonal sense is independent of rigorous or even approximate appreciation of sounds.

Thus, the impression of a key, in many people, can be completely felt by hearing a piece of music, without them being able to specify the key by the name of its tonic.

On the contrary, “key” usually joins the name of the tonic to specify either the established key or the predominant key of a piece. The different keys being only various transposition of the two modes. In addition, this word also applies to the register or the tuning of an instrument relative to the pitch.

Finally, its used to designate the interval of a major second.

(Editor’s Note: The original word for “key” here was “ton.” While in the text’s original language (French) these statements are true, this word has been substituted for clarity.