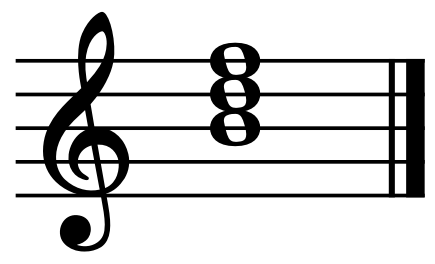

The root of the dominant seventh chord is often suppressed, either for melodic interest or an insufficient amount of parts. The result is a diminished fifth chord:

which is the same as the 7th degree chord of the two modes, and the 2nd degree of the minor mode. However, it differs in character and tonal influence (see Ch 9).

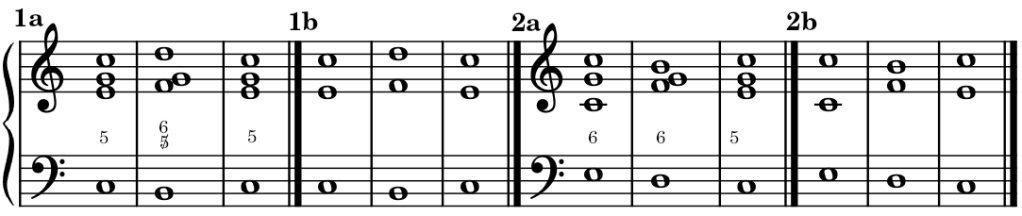

To prove this, compare the harmonic formulas of Ex. 1a and 2a made in four parts, and the same formulas reduced to three parts in Ex. 1b and 2b. The chord B,D,F, (Ex. 1b) or D, F, B (Ex. 2b) gives the feeling of the 5th degree and not the 7th, that is the dominant seventh chord without the root. The root has been suppressed in preference of any other chord tone to produce the same effect in Ex. 1b and 2b as in 1a and 2a.

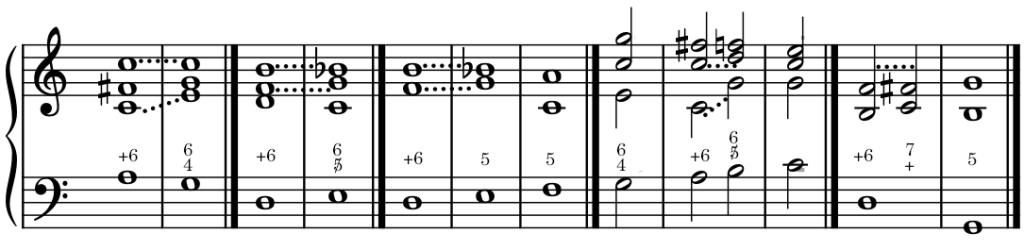

Thus, in these examples, the diminished fifth chord (and its inversion) is the same as the dominant seventh. If its tonal effect is less energetic, its due to the inherent condition of any complete chord. Examples:

To further prove the earlier statements, listen attentively to a harmonic march. The effect of the 7th degree is not very harmonious, and its tonal impression is so weak that the ear only recognizes it instead of the 5th degree without the root because of the symmetry of the harmonic march. Compare that to the diminished fifth chord of Ex. 1b and 2b, a chord whose tonal impression can replace the versions of Ex. 1a and 2b.

As for the chord of the 2nd degree in the minor mode, its tonal and modal character differs greatly from the chord discussed here. Proof of this is found throughout the examples of part 1.

The harmonic formula of Ex. 3a in three parts also needs the root to be suppressed (Ex. 3b). But to complete the last chord (Ex. 3b), its better to use the dissonant note F, whose resolution is more free by the suppression of the root. The realization of Ex. 3b is often used.

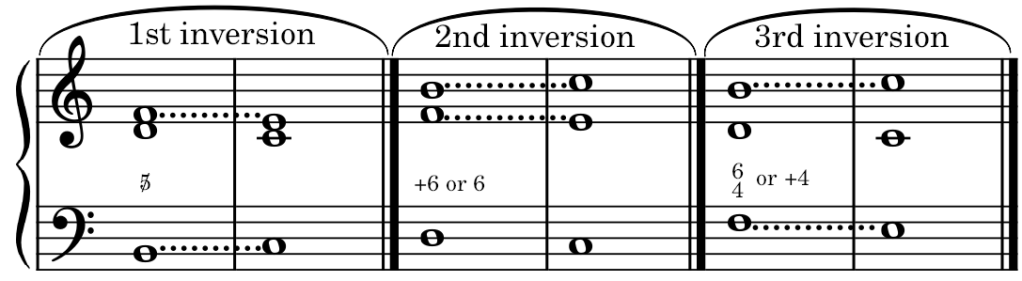

Its obvious that when the root of the dominant seventh chord its suppressed, its no longer in the root position. All that’s left are inversions, which are figured as follows:

Note: These inversions follow the regular resolution in a constrained march.

Its not only in three-part harmony that the root of the dominant seventh chord is suppressed. This suppression can also take place in harmony with four or more parts. In this case, the second inversion is only practiced under the following situations:

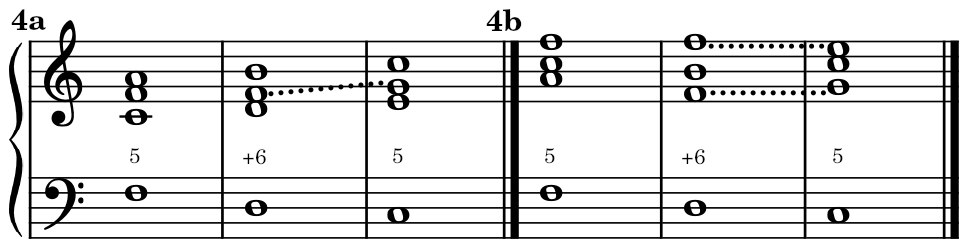

1. When the perfect fourth can’t be prepared (Ex. 4a). In this example, the fifth is doubled (D), but the seventh is also often doubled (Ex. 4b). In this case, the seventh in the upper part resolves regularly, while the other seventh moves up a degree like Ex. 3 (see Ex. 4b).

2. In the rigorous style, especially in counterpoint, every perfect fourth formed with the bass is forbidden. To avoid this, the root is suppressed in the second inversion. Also, the realizations of Ex. 4a and 4b are often used.

Summary

Outside of harmonic marches, a chord having the appearance of the 7th degree is actually the 5th degree and should be attributed as such. The same law also applies to ninth chords. Thus its important this theory is memorized: the summary is only used in harmonic marches (Ch. 11).

Dominant Seventh Chord without the Root vs. 2nd Degree of the Minor Mode

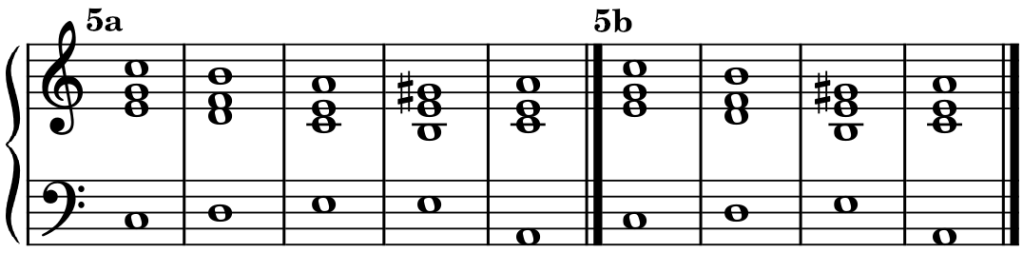

As the appearance of dominant seventh chord without the root and the second degree of the minor mode are the same, it can be used to modulate. By suppressing the root, the dominant seventh chord is weakened, and the ear is more accepting of the change. This suppression allows the chord to be treated as the 2nd degree of the minor mode. Examples:

This irregular resolution of the leading tone B has a surprising effect to the ear. But this exception is allowed because its immediately resolved by the tonal strength of the following chord which determines the modulation to A minor. (see, for Ex. 5a, Ch 7.4, and for Ex. 5b, Ch 10.3).

Conversely, we can treat the 2nd degree of the minor mode as the seventh dominant chord without the root of the relative major mode to modulate. Example:

The peculiarities mentioned in this section have led many authors to consider diminished fifth chords as a mixed chord or a neutral chord (Ch. 1.)

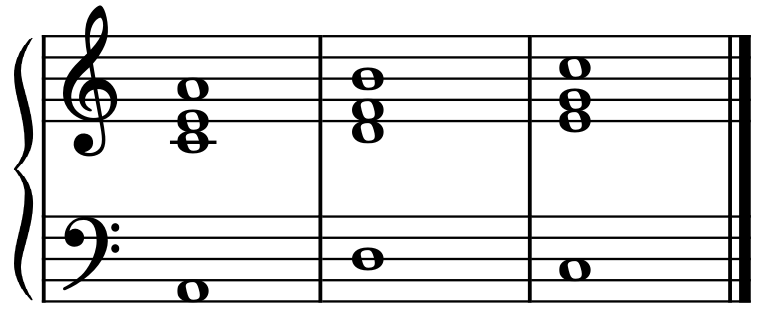

Exceptional Resolutions of Dominant Seventh Chord without the Root

In addition to the exceptions of 5a and 5b, the dominant seventh chord without the root allows for the following exceptional resolutions. Examples: