Resolving the Altered Note

Any altered notes have a natural tendency to resolve to the adjacent degree above when the alteration is ascending, and to the adjacent degree below when the alteration is descending.

Exceptionally, in very rare cases, the altered note remains immobile, or changes enharmonically, to form a chord tone of the next chord.

Resolving the Altered Chord

Like all dissonant chords (Ch. 13.2), every altered chord makes its natural resolution on a chord whose root is at a distance of a perfect fifth below from the root of the altered chord.

However, any other chord may resolve the altered chord, provided the altered note resolves according to the rule above (if the chord contains other dissonant notes, they are subject to the rules of Ch. 13.1). These resolutions are exceptional resolutions.

Realization of Altered Chords

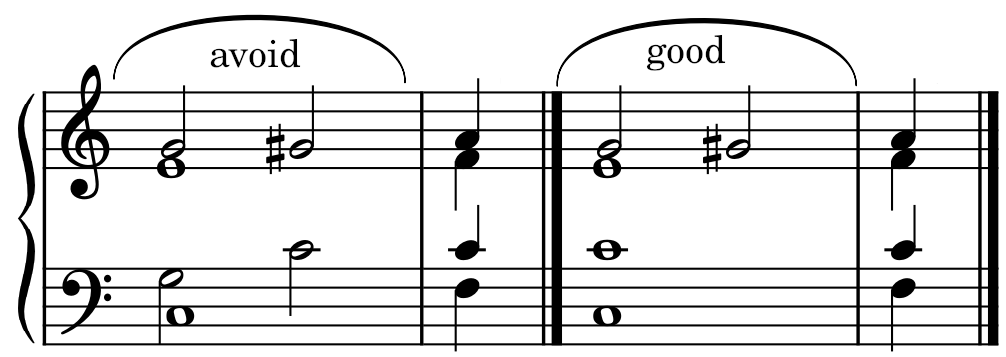

Like any dissonant note, an altered note is never doubled since it has a constrained resolution. Its even necessary to avoid doubling the note to be altered. Examples:

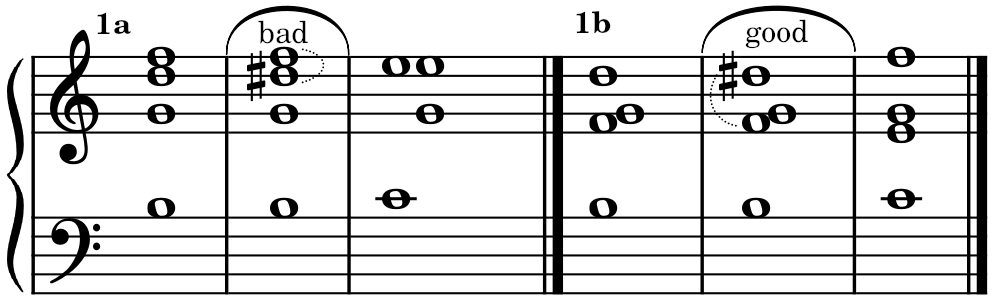

An altered chord can never have both the unaltered and altered note. If certain chords seems to contradict this law, they can never be considered an altered chord. They are always a foreign note to the chord. Examples will be found in the chapters of the second book (Part III & Part IV).

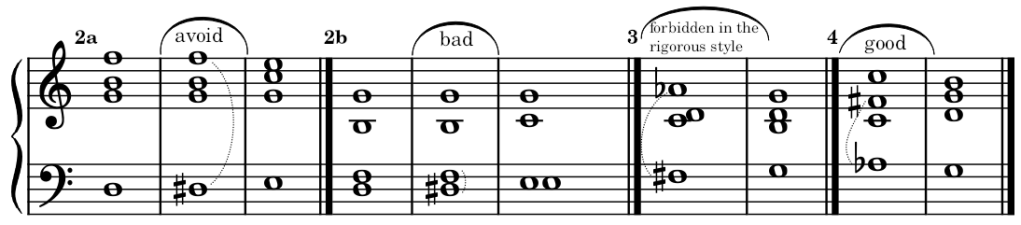

The interval of a diminished third is a result of arranging the notes of certain altered chords (Ex. 1a) or of some inversions (Ex. 2 and 3). This interval is banned in the rigorous style and in schools, as this interval generally isn’t very harmonious and is sometimes very harsh. But its inversion, the augmented sixth (Ex. 1b and 4) has a very good effect. Examples:

Note: The rule needs some restrictions in the free style, as will be seen in 17.3. In this case the inversions which result in the diminished third must be arrange to present the interval of the tenth (Ex. 2a) instead of the third (Ex. 2b).