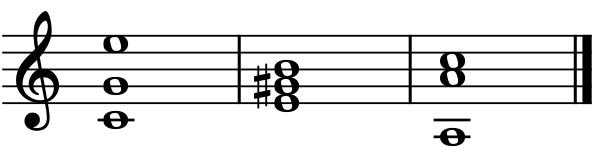

We will clarify the difference between altered chords and chords with accidentals. In the following example:

The second chord (E, G#, B) is not an altered chord. Its a perfect major chord. But if the chord isn’t altered, it can’t contain an altered note. Thus the G#, while preceded by a G natural, isn’t an altered note, but an accidental note, necessary to construct the dominant chord of A minor to determine the modulation.

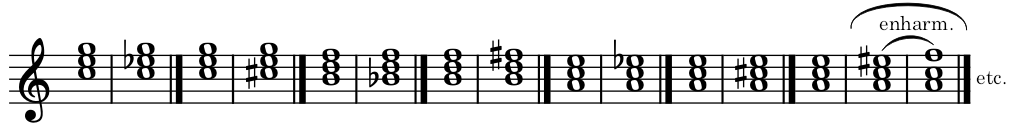

Thus, its well understood that a chromatic change to a note of any chord isn’t enough to result in an altered chord. The following are also not altered chords. Examples:

Each of these examples are only a transformation of a chord into an already known and classified chord (these transformations are also applicable to certain dissonant chords), except the last example, which could be classified as an altered chord. However, its effect is identical to the first inversion of an perfect major chord (F), which is its only enharmonic equivalent.

Altered Chords are chords with a major third and an altered fifth, by a chromatic change ascending or descending.

Altering the fifth of chords with a major third, results in a new kind of chord differing from those made from the natural notes of the scale. Their effect, while dissonant, is accepted by the ear under certain conditions set out in the articles of this chapter. These chords, which greatly enrich the harmony, form real altered chords.

Its possible some altered chords may be created by altering a note other than the fifth in certain chords. But in short, we will only discuss altered chords with an altered fifth, as other chords will make the theory more confusing. These other altered chords will be discussed in detail Ch. 17.4.

Aside from the harmonic combinations mentioned before, any dissonant alteration produces a collection of notes. Its effect as a chord is intolerable and inadmissible. It can only exist under transient conditions of simple melodic alterations, which will be discussed in the chapters dealing with essential melodic notes.

That isn’t to say any combination of notes in the present state of the art, which seems to us inadmissible, can’t be accepted in the future when a new genius has endorsed it in a pleasing application. All that can be said is that the works of the masters only contains examples which exist in the tables of articles 2 and 3 of this chapter (these transformations are also applicable to certain dissonant chords).

These tables not only contain the most commonly used altered chords, but also certain chords, and particularly certain inversion, which are exceedingly rare, and which some are unusual because of their harshness.

Every chord with an alteration retains its original name, but the quality of its fifth is added. Example: major seventh with an augmented fifth. dominant seventh chord with a diminished fifth.

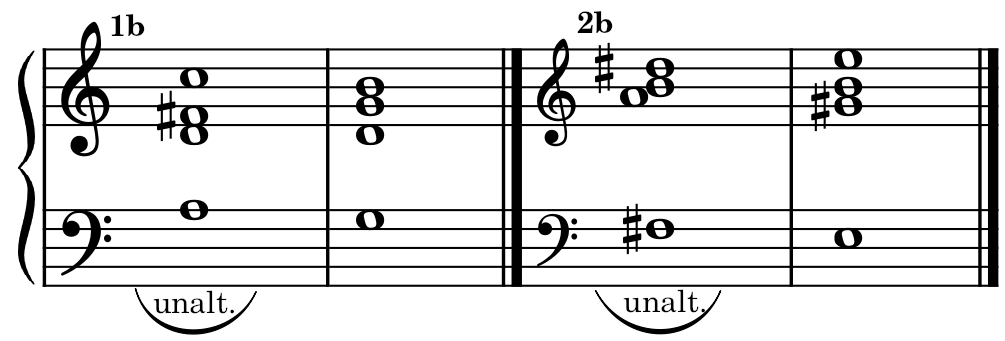

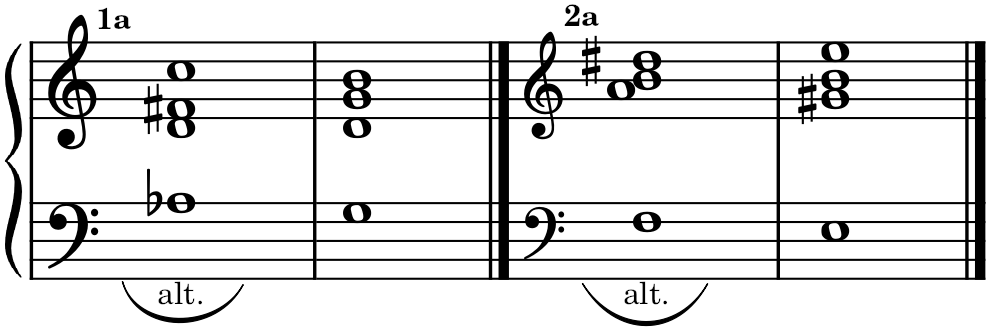

Remark: Its important to point out, for now, altered chords sometimes makes analysis difficult initially. This may because of the key signature, a modulation, or an alteration to a borrowed chord from another key (Ch. 10.6). In these cases, several notes of a chord may appear altered as they may have accidentals. Thus, Ex. 1a contains, in appearance, two altered notes (the A♭ and the F#). But its only the fifth of the chord that is the altered note, while F# belongs to the dominant seventh chord of the key of G, and is only an accidental note respecting the key signature.

It also possible that an altered note doesn’t contain an accidental. Thus, in Ex. 2a, the B# contains an accidental. However, the true altered note is the F since its the fifth of the chord (Compare Ex. 1a and 2a to their corresponding examples, 1b and 2b, placed below, whose harmony is unaltered). Therefore, always go back to the formation of chords (Preliminary Notions, 4), in order to find the root of any altered chord. This way, one will never confuse an altered note with accidental notes () and the definition of altered chords above is justified.

Note: The distinction between altered and accidental notes is very important (Ch. 17.1), as the altered note must never be doubled, while an accidental note may be doubled, unless its the leading tone (Ch 2.4).

Examples:

With an altered chord.

Same harmony, unaltered.