Alteration applies to any chromatic change made to a note. It isn’t necessarily the accidental that signifies an alteration, but the relationship between the notes. It is difficult to differentiate notes with accidentals and altered notes in our musical language.

Alteration means certain modifications, of certain combinations, either melodic or harmonic, wherein the modified note(s) no longer fits into either of the two modes.

Alterations are either ascending or descending, depending on the chromatic change.

Alterations can be either melodic or harmonic.

In melodic cases, the alterations rarely have a long duration. It can be applied to all kinds of notes, real or accidental. It can take place in several parts at once (discussed later in the chapter of melodic notes).

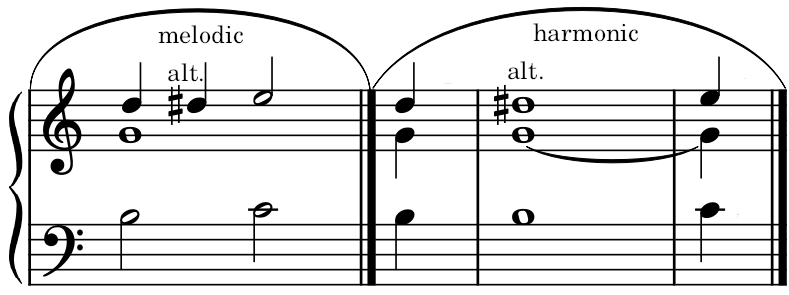

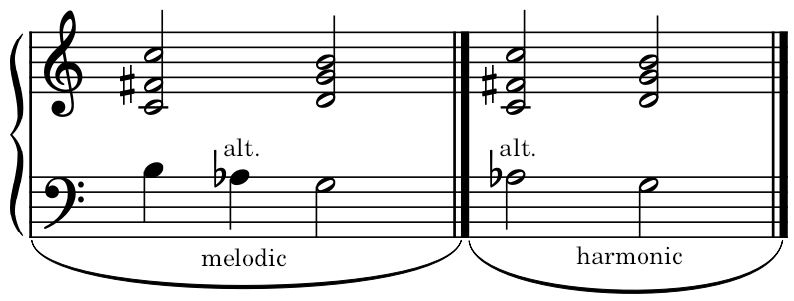

In harmonic cases, it rarely affects more than one note of the chord and produces altered chords whose duration is arbitrary and sometimes very long. Sometimes an analysis may consider certain alterations as melodic (passing notes) or harmonic indifferently. However, an alteration is generally regarded as harmonic only when its duration has some importance and its on a strong beat. This difference is demonstrated by comparing the two version of the following examples. Examples:

That said, some melodic alterations can occur on the strong beat, shown in the appoggiatura article. In short, alterations are melodic when it affects melodic notes, such as appoggiatura, passing notes, etc. regardless of their place in the measure.

Essentially, melodic notes are considered altered when the aren’t diatonic (they don’t belong to the current key set by the harmony). There are two kinds of altered melodic notes:

- They help modulate, and help determine the diatonic order of a new key.

- They are chromatic and don’t affect the current key, as chromaticism is all keys, or in other word, belongs indistinctly to all keys. This is why a chromatic melody can sometimes be accompanied by a purely diatonic, or unitonic harmony (harmony in one key).