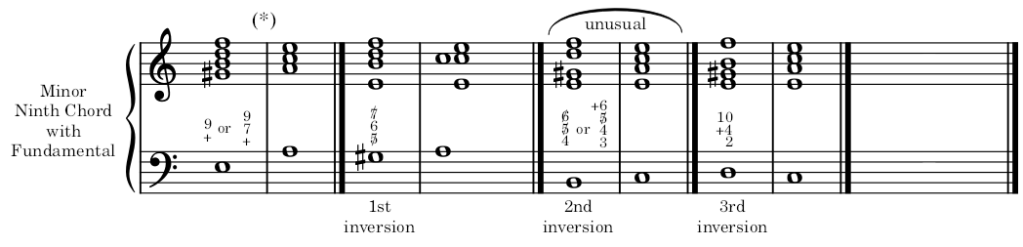

Same with the major ninth chord, the ninth in this chord must always be placed above the root at an interval of at least a ninth. But the position of the third is arbitrary in that it can be placed indifferently, either above or below the ninth. This allows the fourth inversion when the root of the chord is suppressed.

Here are the figurations for the major ninth chord and its inversions:

Note: Regarding the resolution of this chord, comply with the instructions of Ch. 15.0. Similar to the exceptional resolution of the major ninth chord, the resolution of the ninth is often made before the other notes (Ch. 15.1).

The minor ninth chord isn’t often used with its root, especially in inversions. Its plaintive and heartbreaking, far from the sweetness of the major ninth.

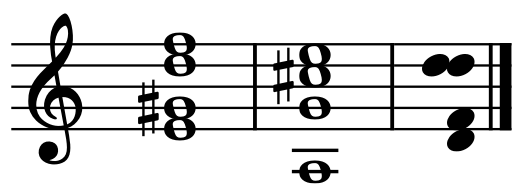

Exceptional Resolution

The following resolution is the only one that can be pointed out.

Minor Ninth Chord without Root (Diminished Seventh Chord)

Without the root note, this chord is called the diminished seventh chord. It’s extremely used and its exceptional resolutions are numerous by ascending or descending chromatic changes. This change can be applied to all notes simultaneously, or only to some parts, while the rest remain stationary.

These exceptional resolutions often provides easy methods to modulate to distant keys. This caused the excessive abuse of the diminished seventh chord in a great number of modern works. To counter this abuse, its important to keep in mind the relations of the main key with the keys modulated to (Ch. 10.4).

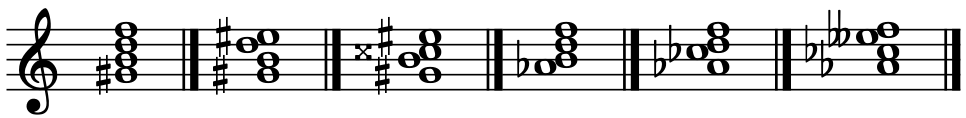

This chord, according to the goal of the modulation, can be written enharmonically in various ways. Examples:

All these chords on a tempered instrument produce the same effect. However, each of them belongs to a different key (The student should name they keys they belong). To write them correctly, one must be aware of the current key. When borrowing the chord, deviate as little as possible from the notes belonging to the relative key. But when the goal is to modulate, write the chord in the most favorable way to the modulation, avoiding enharmonic changes, which always makes reading more difficult and leads to errors in execution. Examples: (*)

In short, however the diminished seventh chord is used, it mustn’t be forgotten that it isn’t a seventh chord but really a ninth chord, of which 3 notes have a constrained march (see Ch. 15.0).

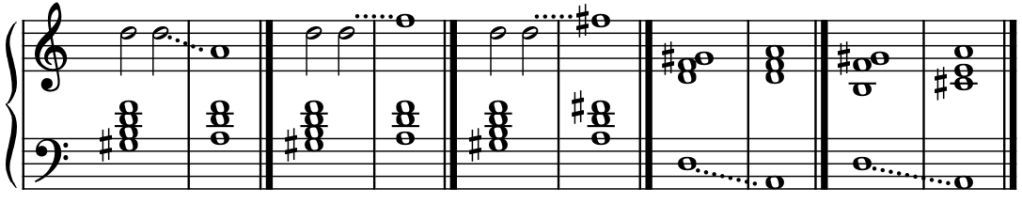

Exceptional Resolutions

The exercises of this article contain most of the exceptional resolutions of the diminished seventh chord.

As for other exceptions, the following are the most used, but are generally only practiced in an extreme part. Examples:

Remark: The major mode often borrows the ninth chord from its parallel minor mode, especially when the root is suppressed (diminished seventh chord). On the contrary, the minor mode cannot borrow the major ninth chord without imposing the major mode (Ch. 10.6).