The position of the notes in this chord must follow these rules:

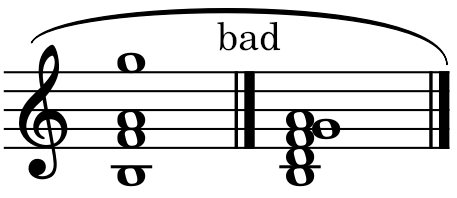

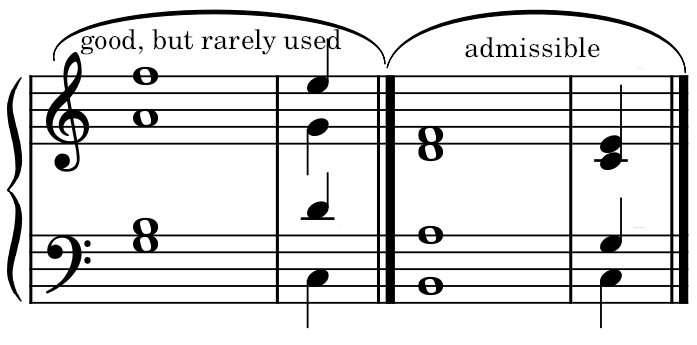

Rule 1: The ninth must always be placed above the root, and separated by at least a ninth interval. In other words, the root can never be placed above the ninth. These two notes cannot have an interval of a second between them. Examples:

Rule 2: The third of the chord can never be placed above the ninth. Thus, the ninth must always form at least a seventh interval with the third. Examples:

These conditions are absolutely essential to the good effect of this chord. These conditions never allow the fourth inversion, even when the root is suppressed.

The major ninth chord in the root position is the peak natural and complete chord because its produced by the resonance of a sound body (see Introduction). This chord, while not consonant, is extremely harmonious. But its chord tones have a very limited motion because of the three notes with a constrained resolution. Moreover, the chord is subject to the rules listed above. These rules make this chord difficult to handle, and cases where it can be used advantageous are rather rare. It doesn’t lend itself to short durations, and its primary charm consists in a sufficiently long duration for its resonance to penetrate the musical feeling.

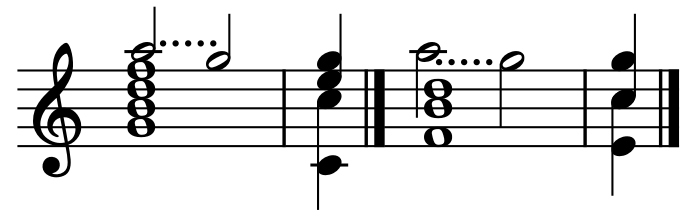

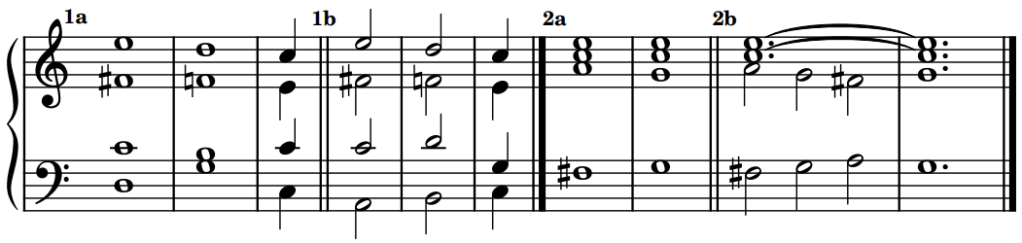

Here are the figurations for the major ninth chord and its inversions:

The resolution of the ninth is often made before the other notes. Examples:

In the last case, its simply transforms into the dominant seventh chord.

The ninth, while always preferably placed in the extreme upper part, can also be placed in an intermediate part provided the arrangement of the chord conforms to the 2 rules at the start of this article. Examples:

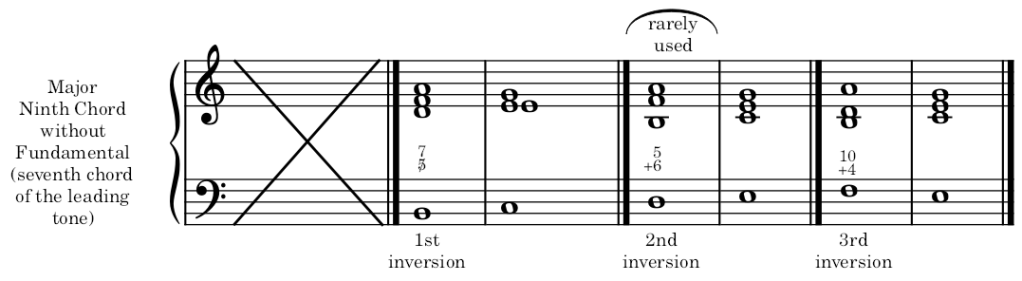

Major Ninth Chord without the Root

The suppression of the root is very frequent in the major ninth chord. Its then commonly called the seventh chord of the leading tone, an improper denomination, as this chord shouldn’t be confused with that of the 7th degree (14.2), whose root is the leading tone, doesn’t have a constrained march, whose dissonance requires preparation, suitable for all inversions, and is only used in harmonic marches (14.3).

Its also important not to confuse the major ninth without the root to the 2nd degree chord of the minor scale. This chord, in addition to the required preparation of its dissonance and a freer positioning of its notes, presents a completely different modal and tonal character.

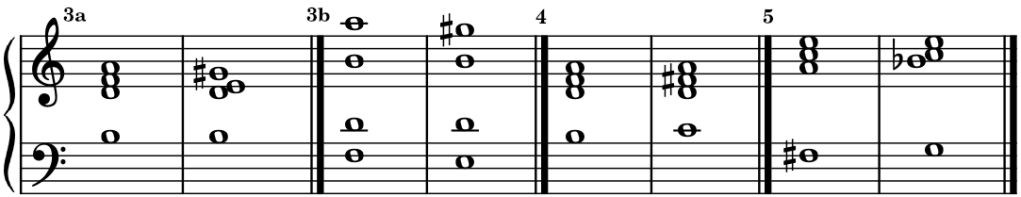

However, the reflections of Ch. 14.2 can be applied to the major ninth chord without the root. This gives rise to the exceptional resolution Ex. 3, and the exception Ex.7.

Exceptional Resolutions

The exceptional resolutions of the major ninth chord are not numerous. The following are the most used:

The following exceptions have a good effect

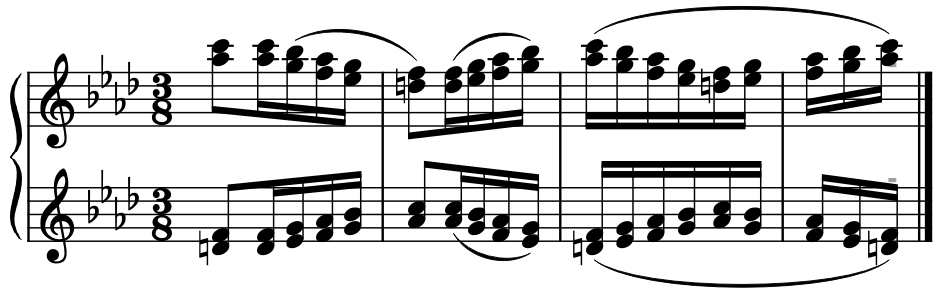

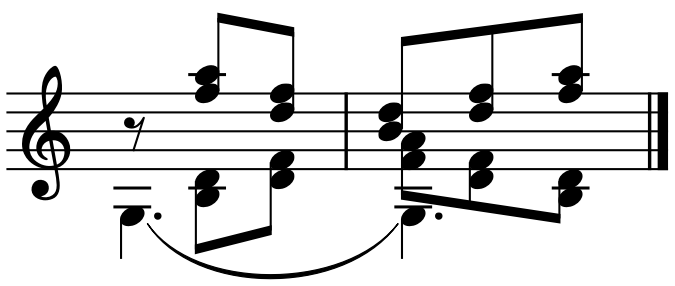

Some modern authors, like Beethoven’s example, have sometimes placed the ninth below the third (so the two notes are adjacent), but not without previously placing the chord in its normal position. Example:

from Beethoven’s 5th Symphony