Preparing Dissonant Notes

Rule 1: Preparation of Dissonant Notes

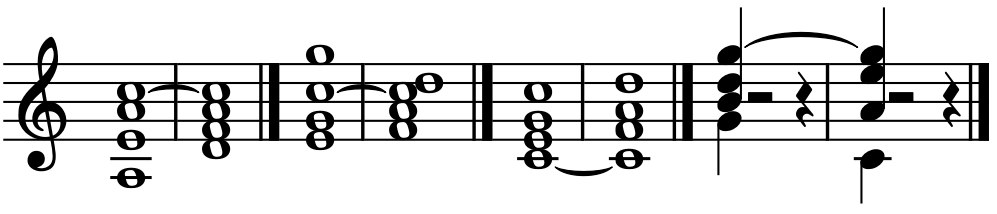

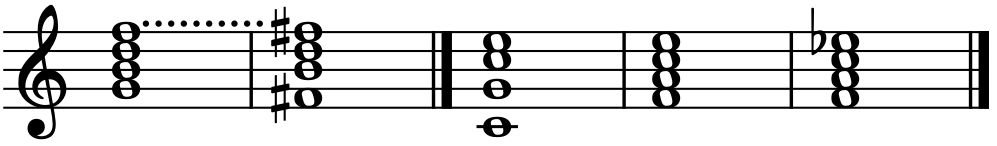

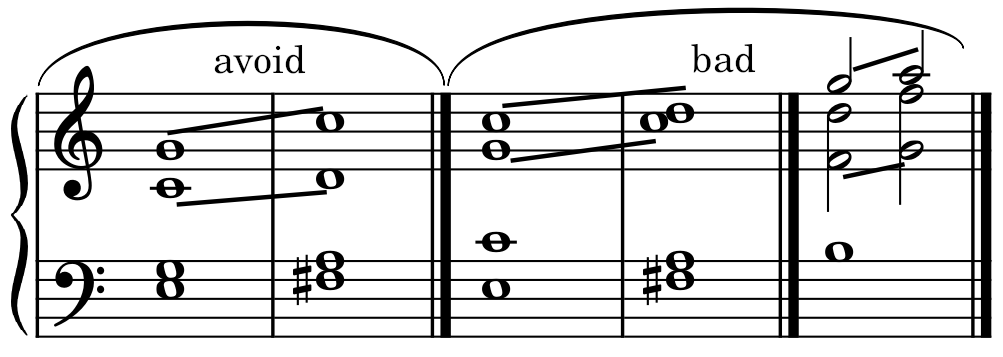

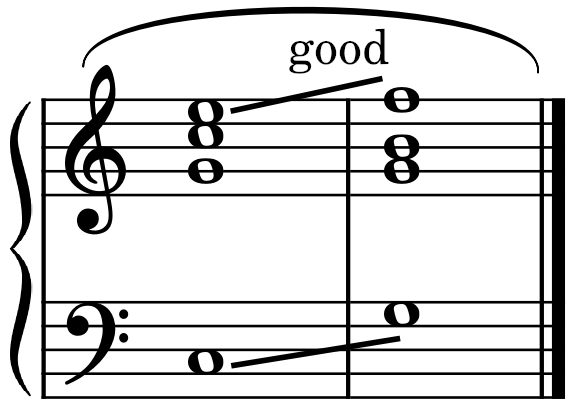

To prepare any dissonant note, it must be an extension or repetition of a note of the previous chord. Example:

Exception: The dissonant notes of dominant chords in the two modes are the exception.

Note: Its important not to confuse preparing the dissonant note with preparing the fourth (7.3). For the fourth, either note of the interval can prepare it, while in dissonant chords the dissonant note itself needs to be prepared.

Observations of Rule 1

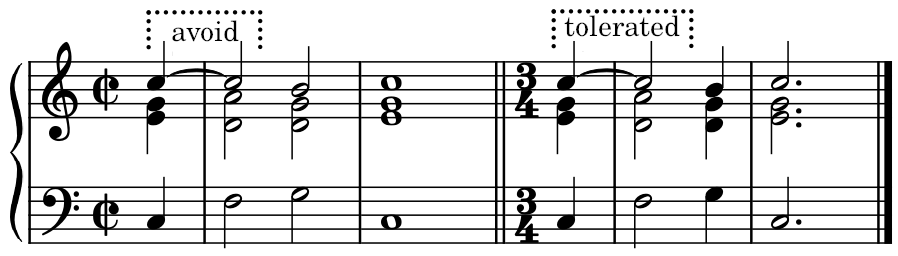

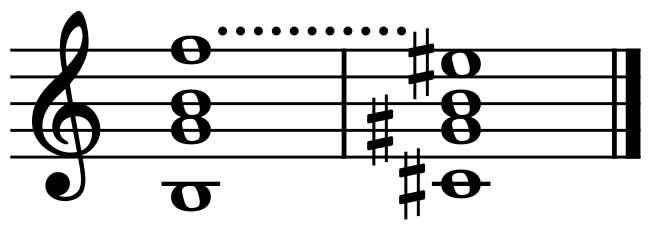

Observation #1: The preparation must at least be as long as the dissonance. This condition is only strictly observed in the rigorous style. In any case, it’s more essential in binary rhythms than in ternary rhythms. Examples:

This preparing a dissonant note this way is what is commonly called a Limp Bond. The effect of the limp bond is less noticeable when the notes have longer values or the tempo is slower.

Observation #2: A dissonant chord is preferably placed on a strong beat of the measure. This observation becomes an requirement in the rigorous style, unless a series of dissonant notes alternate between between the strong and weak beats. — In general, the strong beat is appropriate for a dissonant is more characteristic, that is to say, harsher.

Rule 2: Resolution of Dissonant Notes

To resolve a dissonant note, it must move to the adjacent note below, descending a major/minor second. This realization is called the regular resolution of the dissonant note. Example:

Exceptions to Rule 2

The following realizations are called exceptional resolutions of the dissonant note.

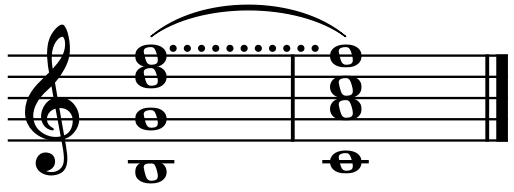

Exception #1: The dissonant note can remain motionless, as part of the following chord. Example:

Exception #2: The dissonant note can resolve chromatically. Example:

Exception #3: This dissonant note can resolve enharmonically, which is rare. Example:

Observations of Rule 2

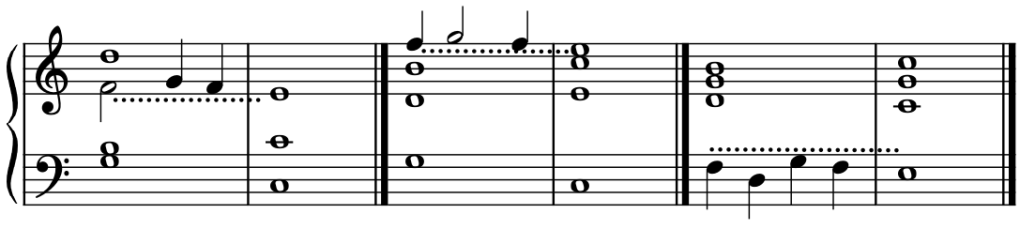

Observation #1: Any dissonant note which doesn’t need to be prepared, may move to a non-chord tone momentarily. Examples:

It may also move to another chord tone, as long as it resolves at the next chord. Examples:

(*) The diminished fifths are allowed here (see 5.2.)

Observation #2: The dissonant note may be separated by its resolution note by: a silence (Ex. 1 and 3), or another chord tone (Ex. 4 and 5.) However, this separation should be short/less pronounced than the dissonant note. Examples:

Rule 3: Regular Resolution of Seventh and Root

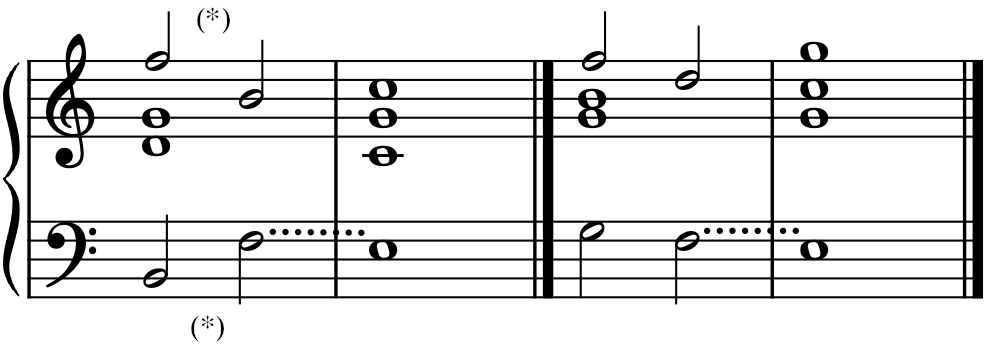

When a seventh note makes is regular resolution, the root of the chord (regardless of where its placed) mustn’t resolve to the same note. Examples:

Cases similar to the preceding examples produce the bad effect of octaves, in spite of the adjacent motion of the upper part and leap of the lower part (Ex. 6 and 7), and even in spite of the contrary motion of Ex. 8.

Rule 4: Avoid Dissonances from Direct Motion

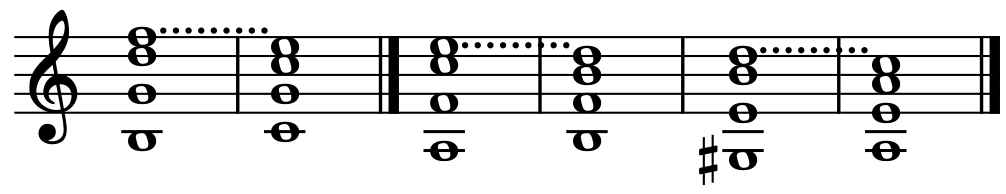

Minor sevenths, and especially major seconds, major/minor ninths must never come from direct motion (While this rule isn’t strict in instrumental music, its always better to follow it.) Examples:

Exceptions to Rule 4

Exception #1: A direct motion can lead to a minor seventh when the upper part moves to an adjacent degree while the lower part leaps. Example:

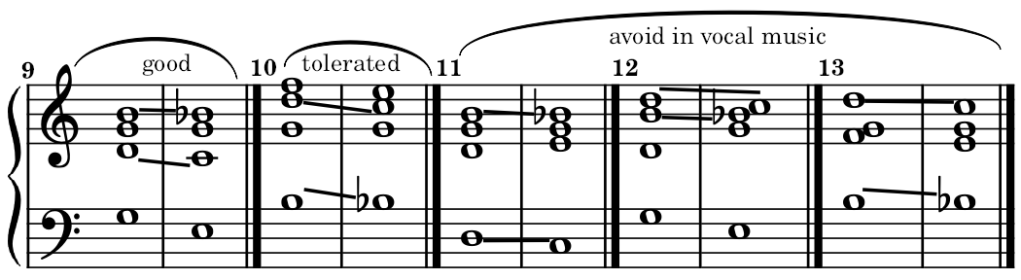

Exception #2: Direct motion may also end in a minor seventh/major second when one part makes a chromatic part while the other part moves to an adjacent degree. In the realization of this exception, the dissonance of the seventh (Ex. 9) is always better than that of the second (Ex. 10, 12, and 13). Furthermore, avoid placing the notes forming the dissonance in the extreme parts (Ex. 11, and 12). Lastly, regarding the second interval (Ex. 12), its preferable to form a ninth interval. Ex. 11, 12, and 13 are hardly used in instrumental music. Examples:

Note: The preceding rule and its exceptions only applies to chords with dissonances that don’t require preparation. This is why intervals of a major seventh and a minor second must always be prepared.

As for diminished seventh and augmented second, modern composers generally approach them by any movement. Nevertheless, mainly in vocal music, the previous rule and its exceptions should utilized as much as possible. In counterpoint, fugue, and the rigorous style in general, preparing the diminished seventh and augmented second is required.

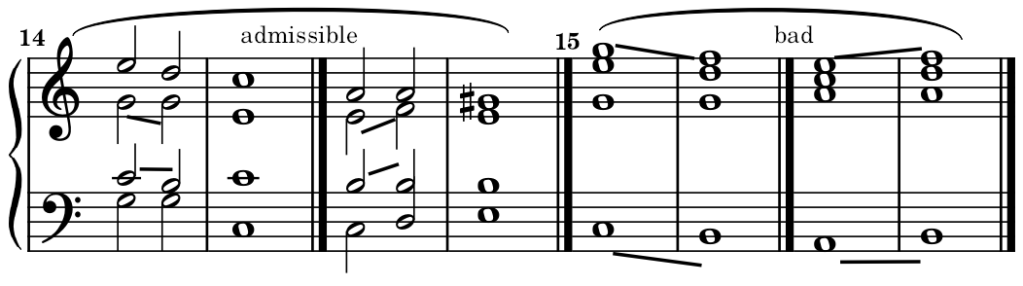

The preceding rule also applies to diminished fifths and augmented fourths in the rigorous style. But in simple harmony, this rule isn’t generally observed with these intervals, except when the diminished fifth is formed by the extreme parts (Ex. 15.) Consequently, a diminished fifth may be substituted for a parallel perfect fifths (Ex. 14.) That said, this exception isn’t tolerated in some schools.

Doubling and Suppressing Notes in Dissonant Chords

Like consonant chords, preferably double the root note. Sometimes double the fifth, rarely double the third (2.4)

As for dissonant notes, generally, they aren’t double because of their constrained resolution. However, when it remains motionless, to a chord tone of several consecutive chords, it can be doubled, even tripled, etc. according to the number of parts (14.2, Ex. 13.)

The fifth is preferably suppressed.

The third is almost never suppressed, except in dominant seventh chords in both modes (2.4.)

Suppressing the root can only occur dominant chords in both modes.