A chord is dissonant when it consists of more than three notes.

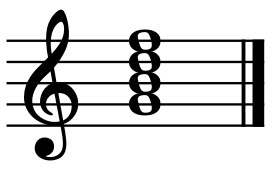

In the root position, a fourth note forms a seventh interval with the root note. Thus, the chord is called a seventh chord. Example:

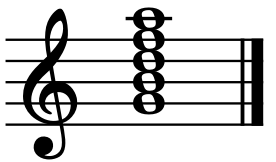

A fifth note forms a ninth interval with the root note. Thus, the chord is called a ninth chord. Example:

Any dissonant interval (Preliminary Notions 1), that is part of a chord, renders the chord itself dissonant. However, the diminished fifth, augmented fifth, diminished third, augmented sixth, etc. aren’t the main cause of the dissonance. Its the between the root and the notes stacked on consonant chords which produce the dissonance.

That’s why the fourth and fifth notes resulting from stacking thirds (see Ex. above) are exclusively qualified as dissonant notes.

Thus, in the language of schools, the word dissonance implies one of the three intervals: the seventh and its inversion the second, or the ninth. This disregards the other dissonant intervals the chord may contain.

The inherent nature of dissonant chords is to provoke a progression to another chord. This progression, from the dissonant chord to the next chord, is called the resolution of the chord.

The dissonant notes in every dissonant chord, and often other notes, have a constrained or forced melodic motion, designated by these terms: resolution of the dissonant note, or, resolution of the note in a constrained motion, depending on the nature of the note.

Thus, resolution applies to the entire dissonant chord, as each note has a constrained motion.

The resolution chord (the chord that resolves the dissonant chord) may be consonant or dissonant.

But a progression of only dissonant chords can only be resolved satisfactorily by ending on a perfect chord.