The resonance of a string or sound tube is undoubtedly the physical and material principle of our music. Many theorists have even pretended, wrongly, our entire melodic and harmonic system is derived from this. Therefore, we believe we must give a brief account on the effects of this acoustic phenomenon which certain harmonic and melodic combinations are based on.

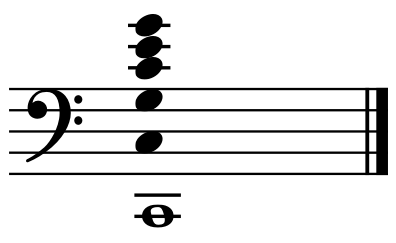

When you vibrate a low note, for example, a low C on a cello or piano, and attentively listen to the resonance, besides the low sound, one immediately and clearly hears accessory sounds called overtones or harmonics. Here is the effect produced:

(Single Note)

(Effect)

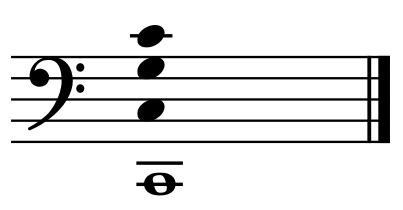

Any somewhat trained ear, if it cannot distinguish the different doubled octaves, will at least hear the following effect:

That is, the octave of the bass sound, its twelfth or perfect fifth, and its seventeenth or major third. In addition, as the vibration of the string becomes weaker, the ear will distinguish, with difficulty, the minor seventh, then finally the major ninth.

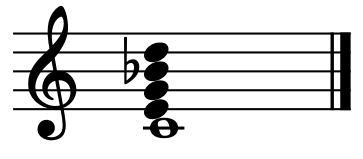

To better understand this chord, we can consolidate these notes into the following arrangement:

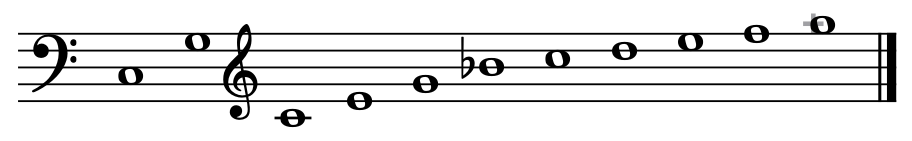

The vibrations of the volume of air contained in an open tube, like a horn or trumpet, invariably produces, according to the intensity or the breath or the pressure of the lips, a series of sounds whose ratios are expressed in the following scale:

Note: Unison, is in fact, not an interval. However, its necessary to include it in the classification of the intervals, since the inverse of the octave is a unison.

But all the sounds of this scale are note precisely accurate. The B♭ is a little too low and the F is too high. Besides there is one more important objection to the system that claims to base our entire music on the natural division of resonant bodies. Its that the entire series of partials of any tube or string we resonate does not give the impression of the minor mode. However, our soul and our senses are just as accessible to the impressions of the minor mode as it is to the major mode.

Based on these statements, there’s only one conclusion: the major mode is the most perfect in that its the closest mode to the natural sonority. This truth will be felt and its application will be found in several parts of this work, that’s why we must state it here clearly. Apart from this obvious fact, whatever is called “natural theory” has only produced unsuccessful dissertations of art.

Whether our modern music system is based on natural or conventional, accept this revelation: our feeling and our musical habits are the consequence. Reasoning will not modify them, and this treaty has no other goal than to seek, analyze, and expose as clearly as possible, all the resources contained in the harmony as it is practiced today (in the 1800s.)

Music, from a modern point of view, is comprised of three elements:

- Rhythm

- Melody

- Harmony

RHYTHM is the sensation determined by the relative ratios of the duration of consecutive sounds, or by the various repetitions of the same or different sounds received by any object. From this, the division of time is born, provided the different divisions are short enough to allow the sensation and the spirit to compare them. The duration of the sounds, the periodic or irregular interruption, the symmetry or asymmetry of their numbers, and lastly, all the possible combinations of values all contribute to produce different rhythms, more or less accented or incisive, more or less vague or languid.

MELODY is the successive emission of an indeterminate number of sounds. Thus, it suffices that two different sounds which immediately succeed each other is a melodic movement.

HARMONY, in the absolute sense of the word, consists of simultaneous emissions of several different sounds.

Each of these elements has a special influence, but their union is necessary for any complete musical work.

Rhythm can exist without melody or harmony, because it can be produced by any kind of percussive instrument. Of these three, rhythm is the most indispensable. Its effect is the most tangible, and for this reason, its influence is felt even on the least refined listeners.

Melody cannot exist without rhythm, but it can exist and charm without the help of harmony. Its origins is in the inflections of the human voice, reflecting the various emotions of the soul. Rhythm and melody are the two elements of music of the ancient civilizations.

Harmony, in regards to its application to art, cannot do without rhythm or melody, unless it involves the simultaneous emission of unchanging sounds. The moment any changes occur in the sounds, it results in a rhythm and a melody.

Thus Harmony, in the broadest sense, embraces the whole of music. It forms a special and distinct special branch of art. It deals specifically with the conditions and laws that govern the concordance of sounds. Its clear then, that the framework of this special treatise on the already complex study of Harmony does not permit the deepening and development of the rhythmic nor the melodic elements. Yet, their influence on Harmony is considerable and constant, and their influence on Harmony has been highlighted as much as possible throughout this work. But many cases are subject to musical intuition to understand and appreciate its influence. “The pupil who does not have this intuition is not born a musician, and, from now on, must close this work.”