The bad effect of direct fifths and octaves is more or less reduced when these intervals are formed by the intermediate parts, or even an extreme part and an intermediate part.

However, it is crucial to avoid having both outer voices move in parallel fifths or octaves simultaneously. These observations applies to all paragraphs in this article except the last.

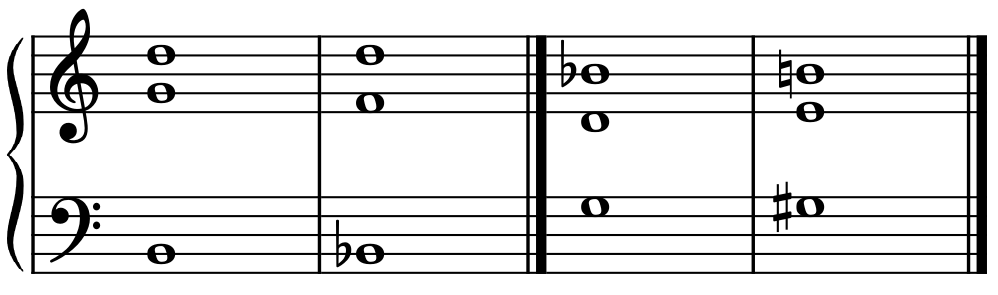

A direct fifth (perfect fifth or octave may result from a similar movement) is allowed when the lower part proceeds by a semitone and the upper part leaps. Example:

This exception is tolerated in most schools, but only in harmony of four or more parts.

A direct fifth is allowed when one part proceeds by a major second and the other by a chromatic semitone. Example:

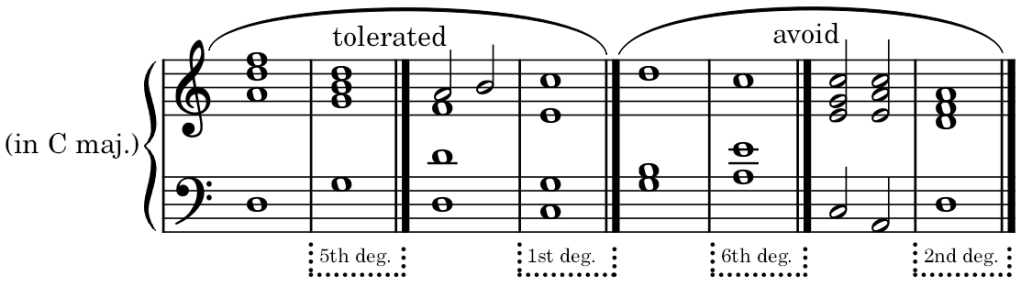

A direct fifth is far less defective when the chord is of a better degree (3.2) than the previous. Examples:

Parallel fifths are far less defective the more they are distant. Examples:

(**) 7.1

Parallel fifths by contrary motion (forbidden in 2.6) are practiced in the free style, especially in harmony with more than four parts.

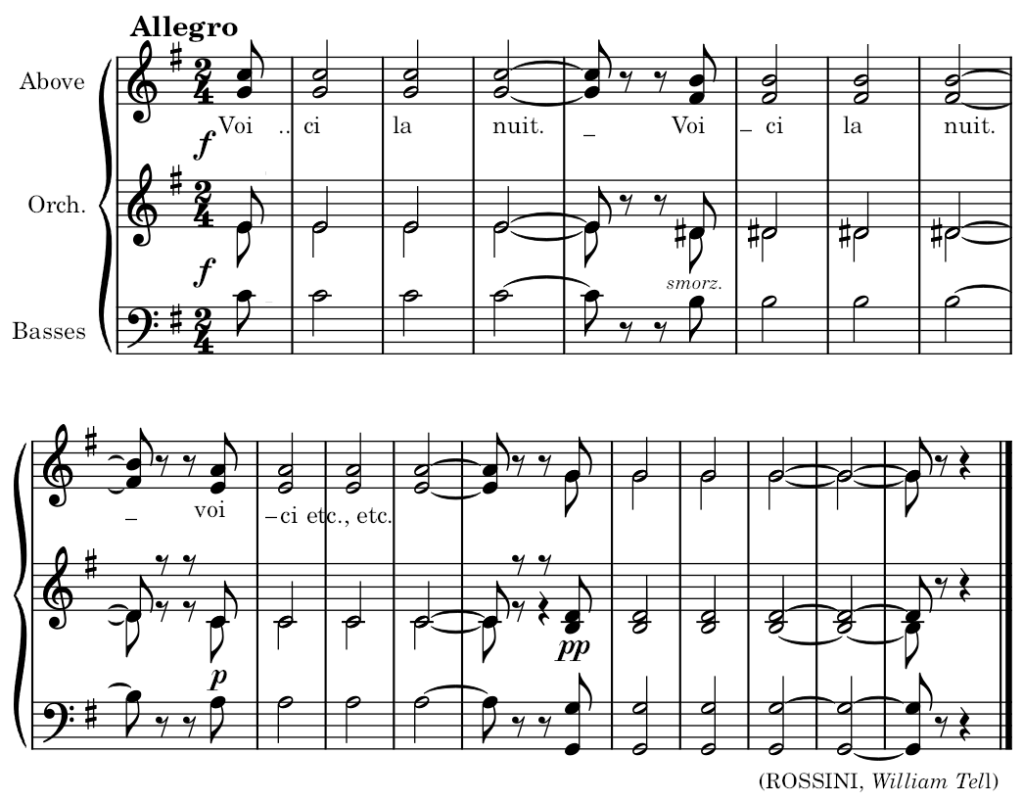

Most authors don’t always respect parallel fifths and octaves when its between the last chord of one phrase and the first chord of the next phrase (the first paragraph of this article isn’t applicable in this case), or even of a member of a phrase to another. These exceptions sometimes have a striking effect, especially when one starts in a different key, every phrase, or even each member of a phrase, however short. Examples:

Note: This use of parallel fifths/octaves not tolerated in school/study.