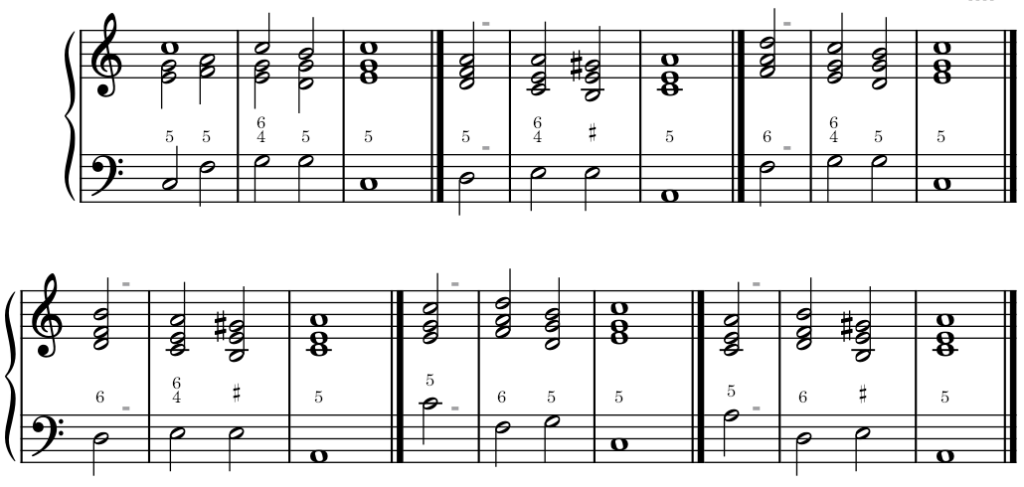

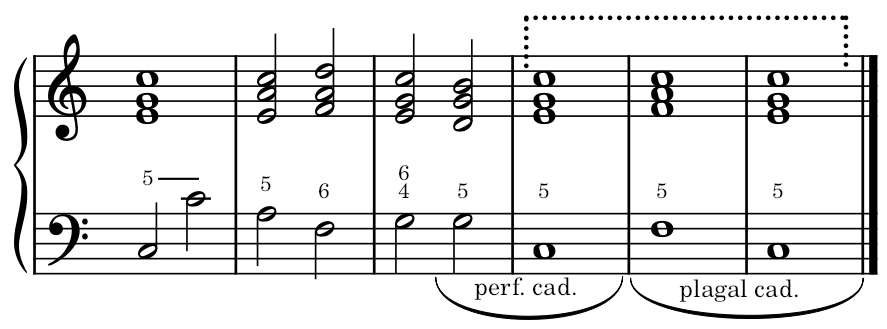

1. Perfect Cadence – ends a phrase/piece with the dominant to the tonic chord, both in root position. Listed below are the common perfect cadences:

The perfect cadence is always better when the tonic note is in the extreme parts. Example:

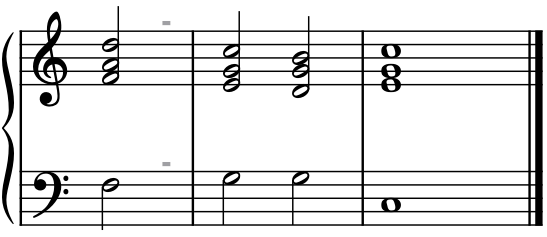

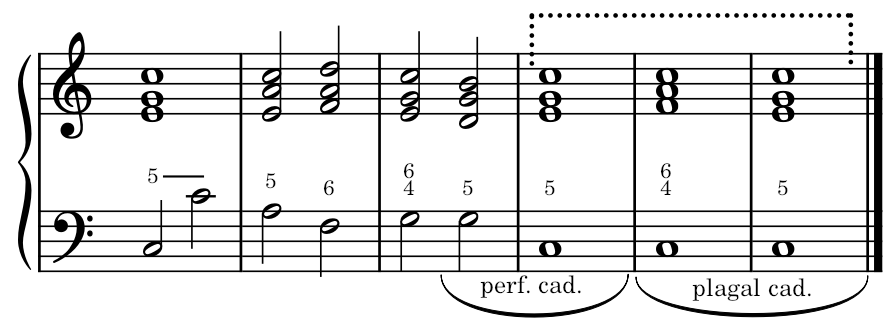

Any other position weakens the perfect cadence, and may even make it imperfect. Example:

This especially applies to the final cadence of a period/piece.

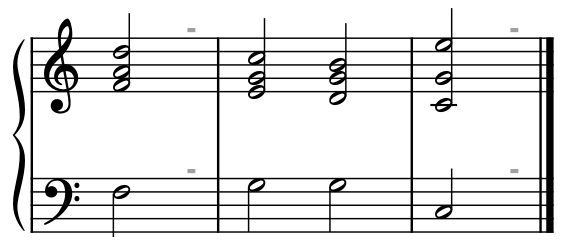

2. Imperfect Cadence – ends a phrase/piece with the dominant to the tonic chord, but either chord is inverted (tonic (Ex. 1) or dominant (Ex. 2)). The perfect cadence is weakened, resulting in the imperfect cadence. This cadence does not end a final cadence, and requires at least another phrase to complement it. Examples:

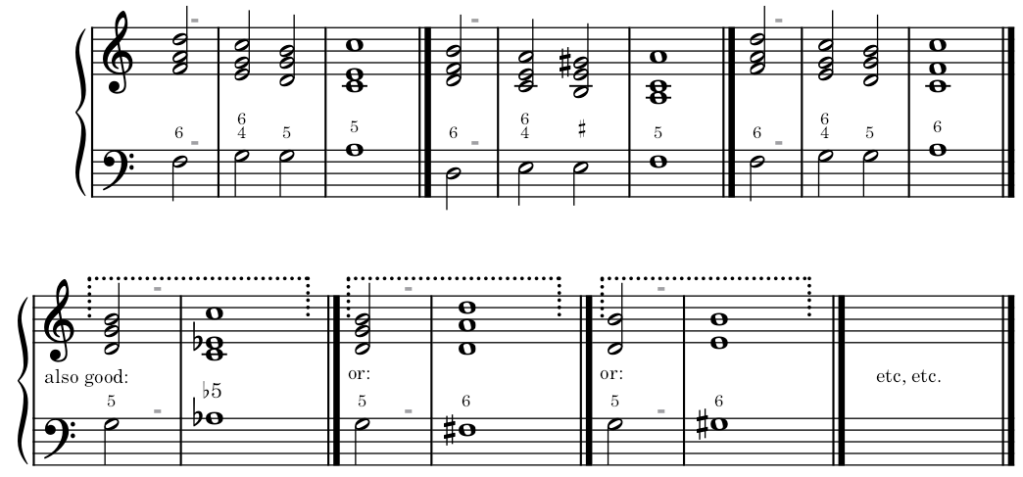

3. Deceptive Cadence – when a period inclines towards a perfect cadence, but instead of concluding on the tonic chord, it concludes on any chord, either of another degree or another tone, consonant or dissonant. Examples:

Many theorists call a Deceptive Cadence only that of the dominant (5th) to the submediant (6th). Any other chord, or any chord foreign to the tone is an Avoided Cadence. This distinction is useless.

4. Plagal Cadence – often employed at the end of a piece after a perfect cadence. End with the subdominant (4th, either in root position or inverted) to the tonic which ends the piece. In this case, the plagal cadence forms a sort of Coda added to the piece. But the plagal cadence can occur without being preceded by the perfect cadence, and can conclude any phrase except the final phrase. Examples:

or

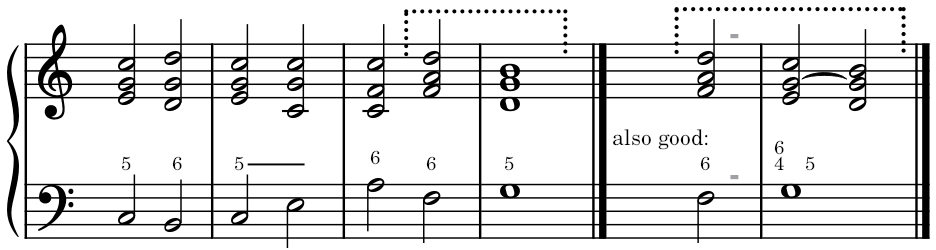

The supertonic (2nd) chord in first inversion can produce the effect of a plagal cadence. Example:

5. Half-Cadence – determines a rest, or sometimes simply divides members of a phrase or period. It most often ends on the dominant chord in the root position, preceded by any chord. Examples:

The progression of dominant to tonic, even in the root position, isn’t always enough to determine a perfect cadence. When this progression occurs too early to give the sensation of a complete phrase, their effect often only amounts to a half-cadence. This effect is mainly dependent on the melodic idea and the overall structure of the period.

The sensation of a half-cadence can be produced by a chord other than the dominant. This can result from certain rests on the tonic (1st), subdominant (4th), and supertonic (2nd.) The half-cadence can also be weakened by either an inversion or other influences.

6. Quarter Cadence – An often dividing cadence between members of a phrase, weaker than the half-cadence, but nonetheless still acts as punctuation.

Other Remarks

A sense of rest or pause can be strongly felt if a part of a phrase remains on a single chord.

Any cadence, whatever the type, is always better felt when its ends on a strong beat. Except for a certain rhythms, the weak beat only allows incomplete rests, like a half-cadence.

Sometimes the chord that ends one phrase may also serve as the start to the next phrase. That way, two phrases become entangled within each other without disrupting their structures (like symmetry. This measure may be counted twice; once for the previous period/member, and once for the next period/member.)