Each part must only contain easy melodic intervals of intonation.

Rule 1: All diminished or augmented intervals, and intervals greater than a minor sixth, are forbidden, except the octave. These intervals are faulty even when an intermediate note exists between them.

Cases with a Good Effect:

(a) If the part is ascending, and the intermediate note is adjacent to the next note.

(b) If the part is descending, and the intermediate note is adjacent to the next note.

Exception: When the second note is the leading tone going to the tonic and is a diminished fourth/diminished fifth, it’s tolerated.

Rule 2: The leading tone in the minor mode must always go up to the tonic. This is not always applicable in the major mode, as it’s only necessary in the cadence of phrases.

Rule 3: In the exercises and the rigorous style, avoid leaping the parts and proceed by adjacent notes. This rule does not apply to the Bass (its laws will be taught in the sequence of chords).

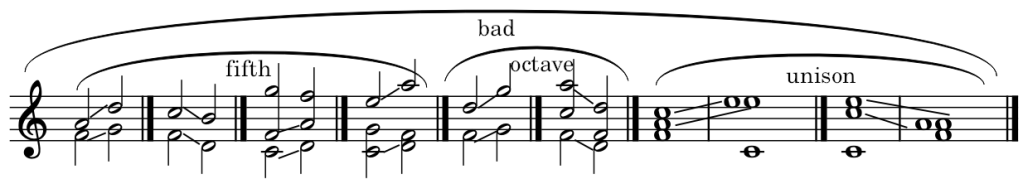

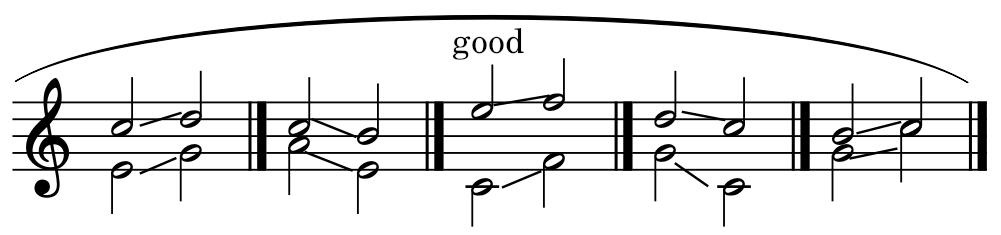

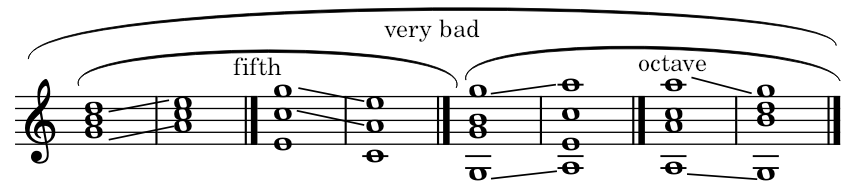

Rule 4: A direct fifth or direct octave (*), which is when two parts result in a perfect fifth, octave, or unison by similar motion, is forbidden. These intervals coming from similar motions generally produce a bad effect regardless of the parts.

Exception: The upper part moves by adjacent notes, and the lower part leaps.

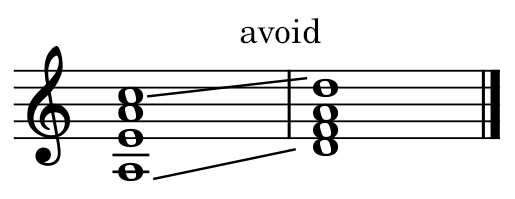

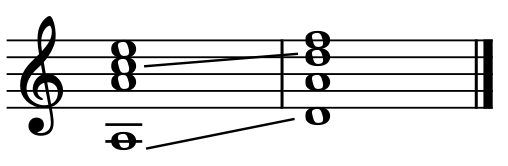

For the octave coming from a direct ascending motion is in the extreme parts, its only good when the upper part moves by a minor second.

When the upper part proceeds from a direct ascending motion by a major second, the result is often unsatisfactory. Example:

However, annoying effect disappears when the octave is not in the extreme parts.

More exceptions are outlined in later chapters.

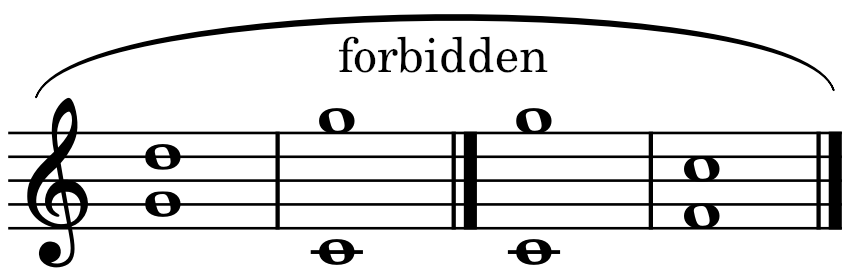

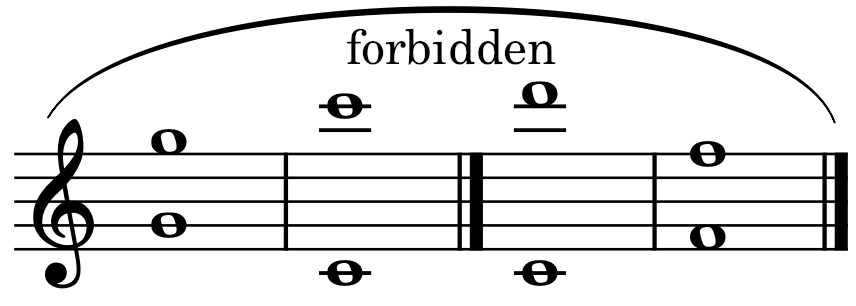

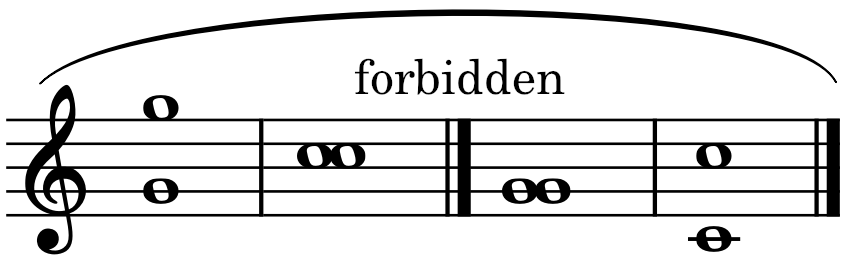

Rule 5: Parallel fifths and parallel octaves, which are two consecutive perfect fifths and two consecutive octaves between the same parts, by similar and contrary motion are forbidden. Since this applies to the octave, it also applies to the unison. Coming from a unison is also forbidden.

The effect of parallel fifths and parallel octaves is even worse than a perfect fifth or octave by similar motion.

Example of parallel fifths by contrary motion:

Example of parallel octaves by contrary motion:

Examples including the unison:

Remark: There’s a distinct difference between parallel fifths and parallel octaves. In general, the parallel fifths are harsh and incoherent. The parallel octaves are poor and hollow. Therefore, the effect of parallel octaves is worse than parallel fifths.

Regarding the series of consecutive octaves which often appears in music, their purpose is to reinforce the melody to make it more pronounced, which isn’t related to the topics mentioned here. This will be discussed at the end of the Part II.