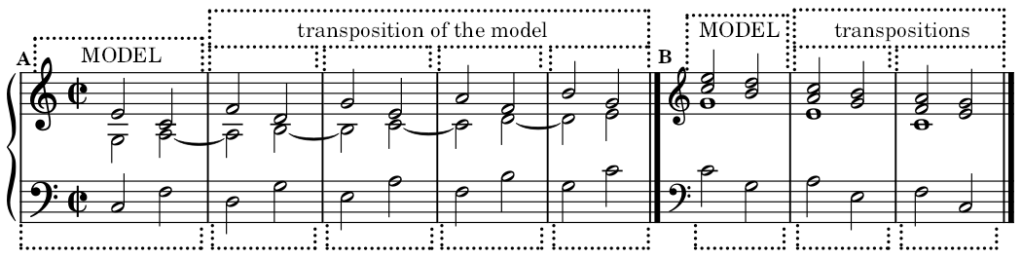

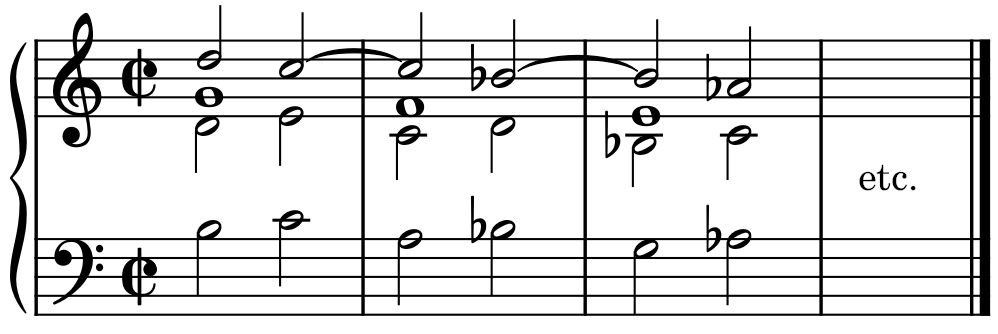

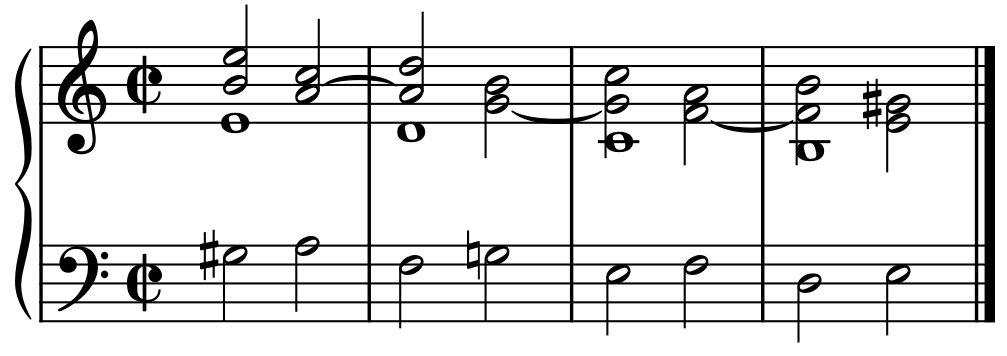

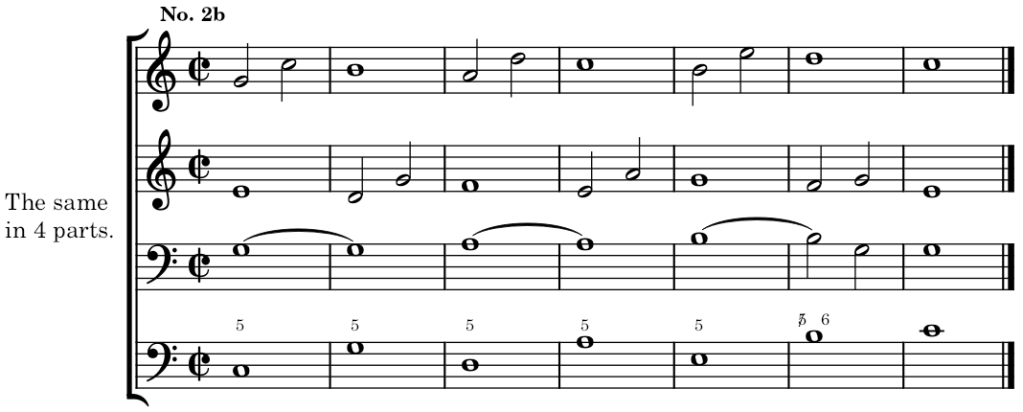

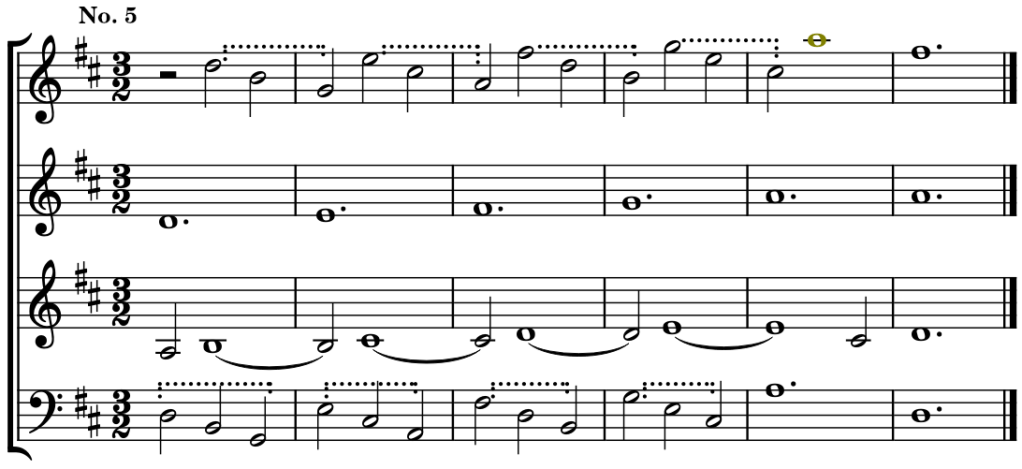

A harmonic march is a repeated harmonic formula, called a model, that is symetrical at similar intervals. Examples:

The same model may result in several different harmonic marches, depending on the transpositions made to it.

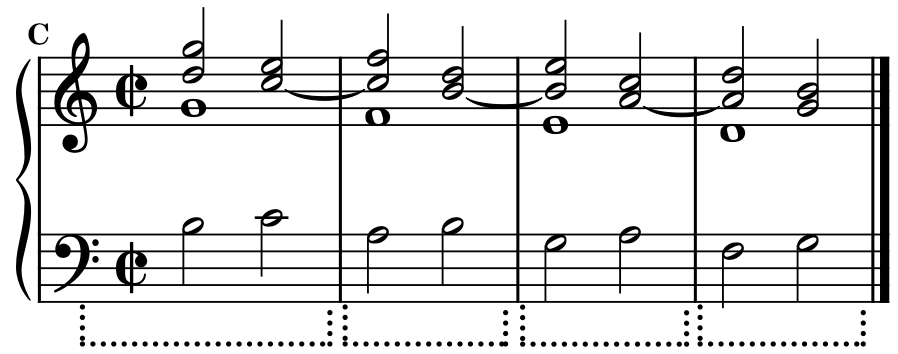

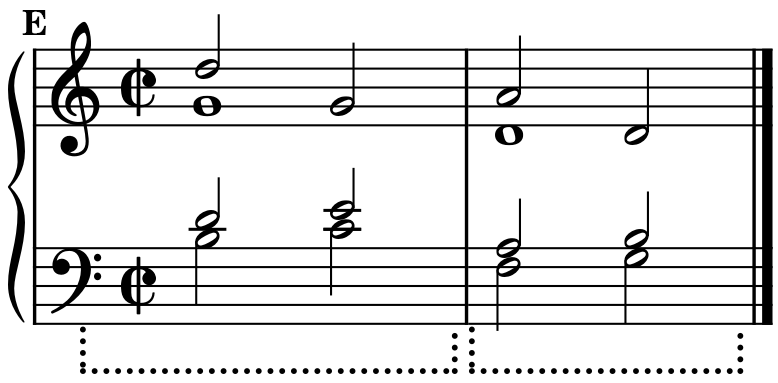

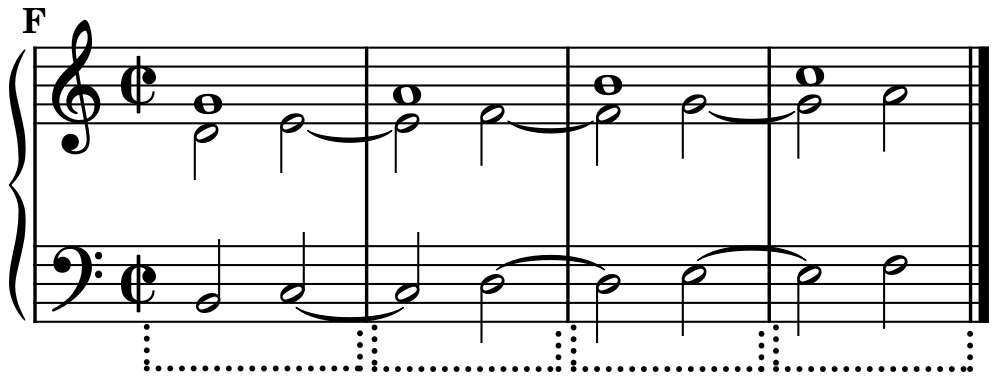

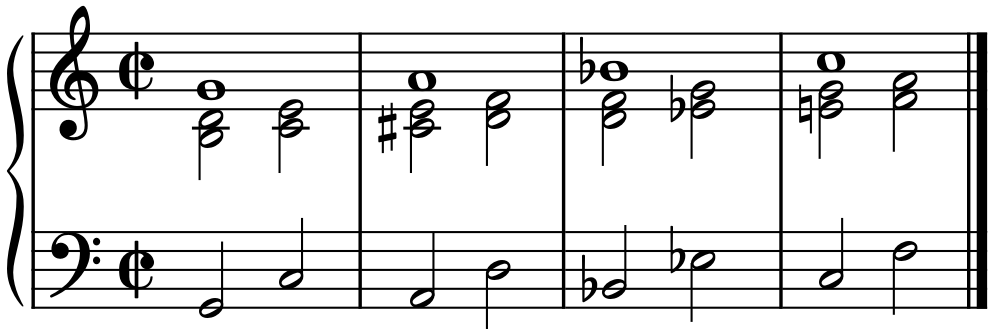

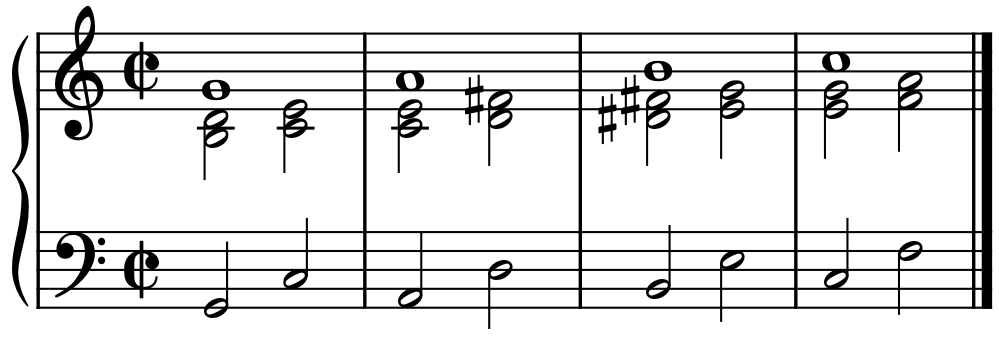

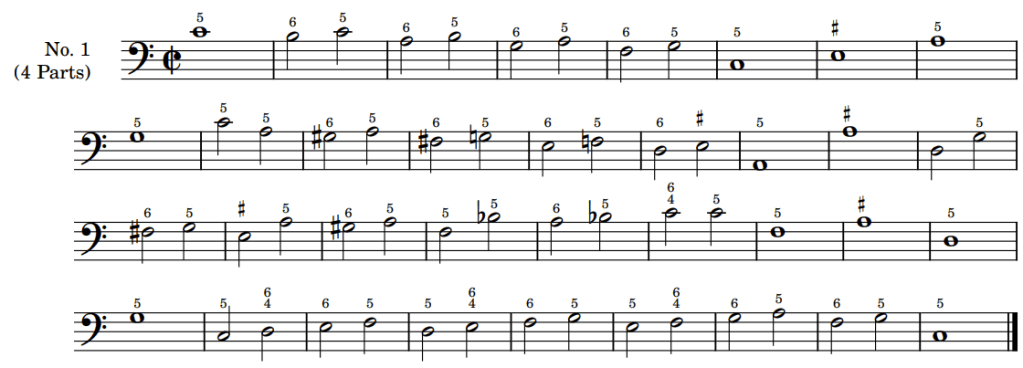

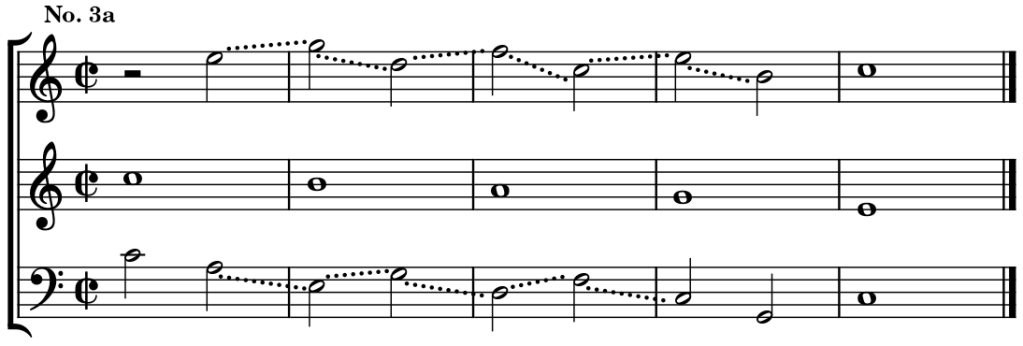

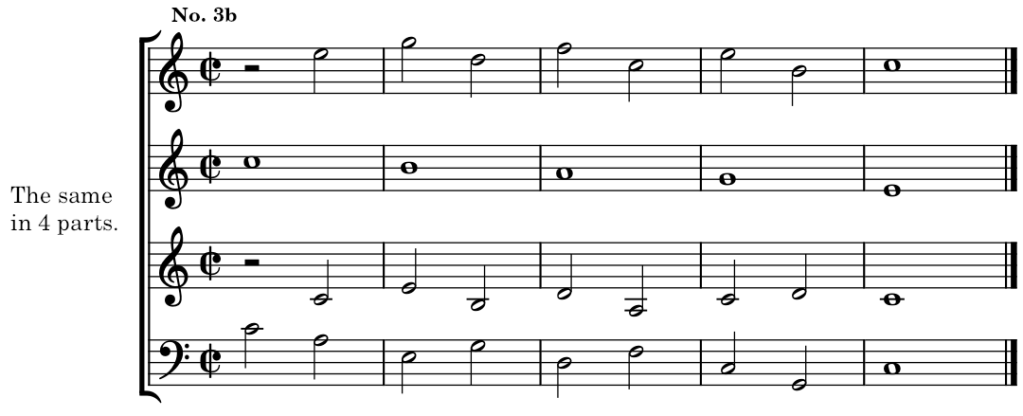

Here are examples based on the following model:

1. Transposed model of lower seconds:

2. Transposed model of lower thirds:

3. Transposed model of lower fourths:

4. Transposed model of upper seconds:

One of the transpositions can be added to the model to form a new model. Example:

The marches of Ex. A, F, G are called ascending, and Ex. B, C, D, E are called descending.

From the previous examples, we see each part in isolation is a regular melodic progression, a consequence of a melodic design or group transposed successively and symmetrically. A melodic progression, in any part, must be treated as a harmonic march. However, depending on the composer’s intention in a fantaisie, a predominant part may have a melodic progression without the regular march of the other parts and without each melodic transposition of the other parts in the same harmony. Thus, there’s no harmonic march.

The constitution of a harmonic march requires the following conditions:

- The model must only form a part of a phrase, never a complete phrase. It may also form a member of a phrase short enough to fit successive transpositions, such that its symmetrical set is easily recognized.

- The progression from the last chord of the model to the first chord of the first transposition exclude any third order progressions (4.3). At most, second order progressions are allowed, but first order progressions are preferred. After the progression from the model to the first transposition, the harmonic march is recognized. Thus, subsequent transpositions do not need to worry about weak progressions or bad degrees.

- A harmonic march can only end with a chord of one of the best degrees. The last transposition may ignore symmetry to end on a satisfactory cadence. However, this is only practiced once the first chord of the last transposition follows the march.

- The model’s realization must be designed so it can be identically realized in each transpostion. For this condition, its enough to ensure the first chord of the first transposition can be arranged exactly the same as the first chord of the model. After which, the sucessive transpositions will necessarily form a regular melodic progression.

Note: The forbidden melodic intervals (diminished & augmented intervals, and intervals greater than a minor sixth) don’t have a bad effect in a march, as they result from a regular diatonic transposition of the different degrees of the scale (see Ex. A, 4th measure of the Bass, and from the 4th to 5th measure in the upper part.) However, the model itself mustn’t have these intervals.

Use of the 7th degree: By performing all the examples in this chapter on a keyboard instrument, the role of the 7th degree will be observed, prohibited thus far, as having a tonal effect so small that its only applicable in a harmonic march. The radical difference between the 7th degree and the 2nd degree of the minor mode will also be noticed. These remarks on the 7th degree are important as it will be referenced many more times in this work.

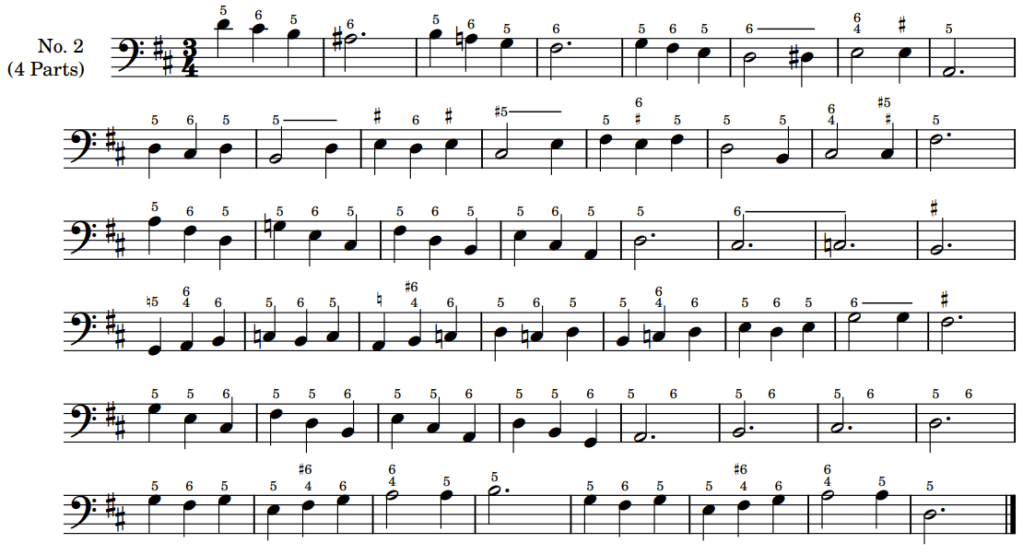

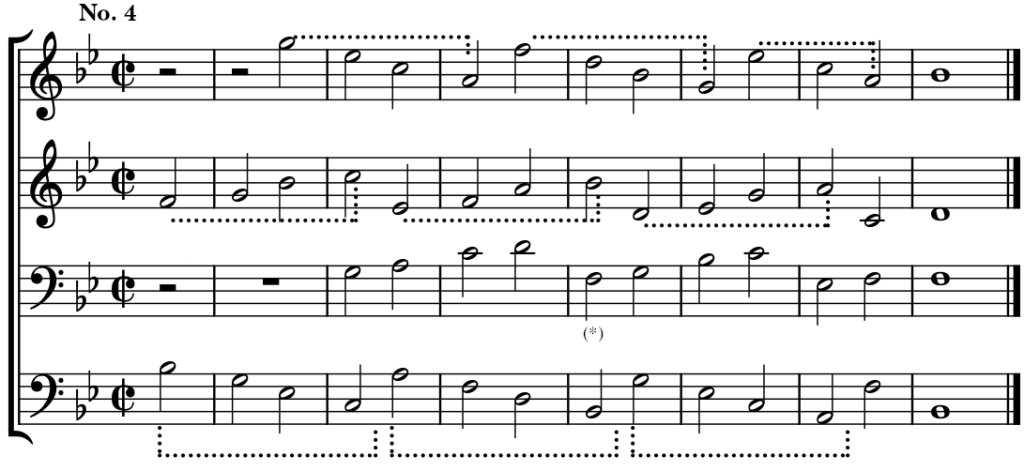

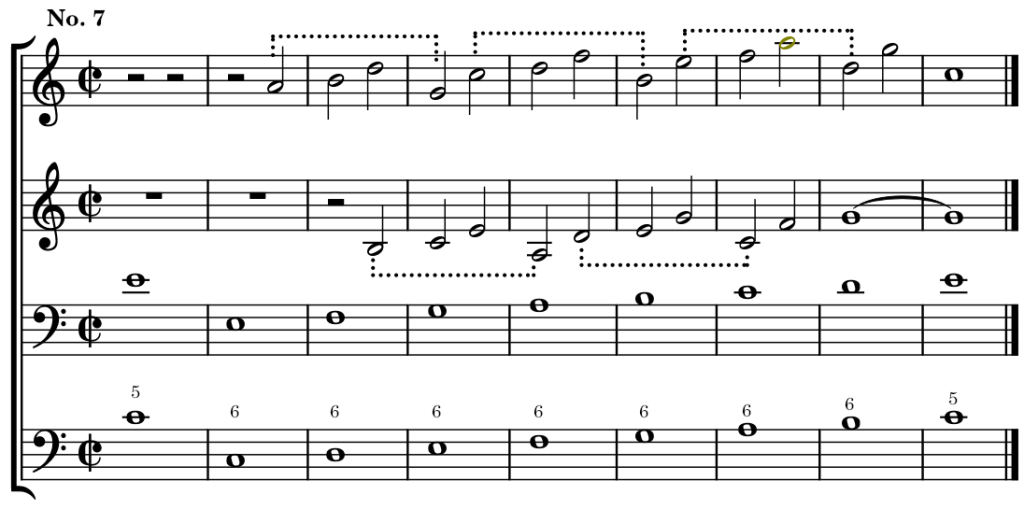

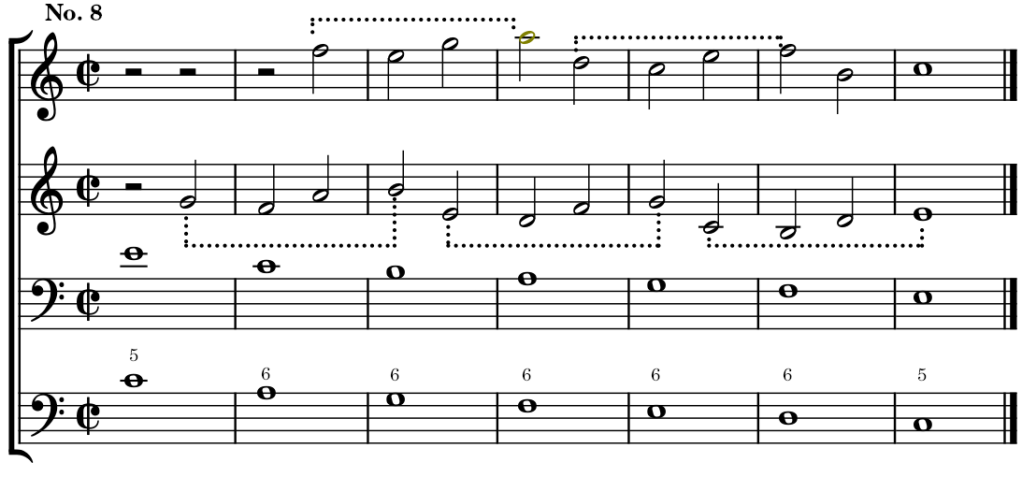

The previous examples of harmonic marches all belong to one key, but a harmonic march can also be use to modulate:

Examples of Modulating Marches

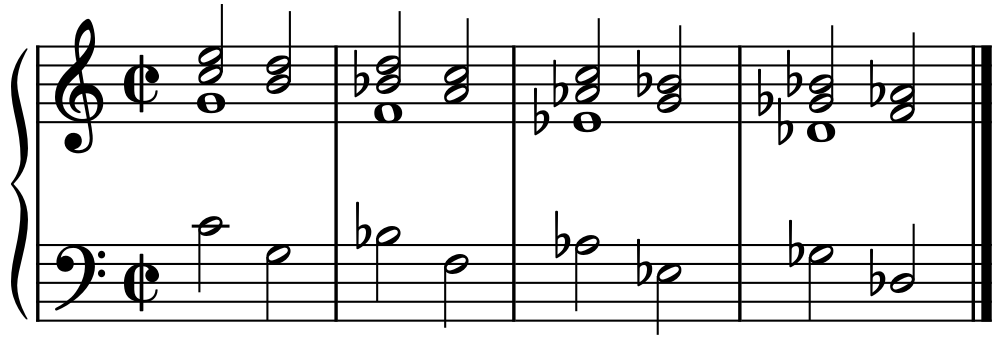

In the minor mode, every harmonic march contains some borrowed chords or some passing modulation to a certain extent. This is because the 3rd and 7th degree of this mode are impractical, even in harmonic marches. Example:

Any second inversion, in order to be used in a model, must meet the conditions of 7.3. Thus degrees which, aside from harmonic marches, don’t allow the second inversion, can be employed without inconvenience if they result from transpositions only in one key. The following Bass (No. 1) serves an example.

Basses to realize

Harmonic marches have great used in the strict style, especially the fugue. However, They can apply to all styles. While their interest is mainly due to its melodic devices and dissonances, its important to study their fundamental construction and grasp their basic mechanism.

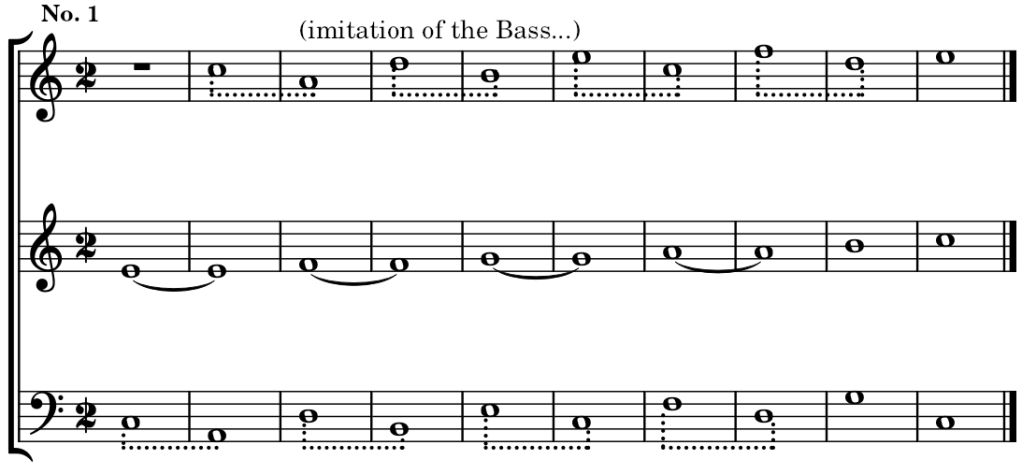

Additionally, one can become familiar with using them through some very simple imitations (see Supplementary Chapter) that include the following steps:

(*) Regarding the parallel fifth, see the Supplementary Chapter.

The sequence of sixths (7.1) either ascending or descending can only be realized in four parts by using imitations, which converts them into harmonic marches. The following examples offer the simplest realization of these kinds of marches, which become more interesting by adding suspensions and melodic notes (discussed in the parts 3 & 4), where the same marches are reproduced with various realizations.

Summary

Harmonic March – a harmonic formula reproduced successively, in a symmetrical order at similar intervals, on different degrees of a scale.

Transpositions of Harmonic Marches

- Lower Seconds

- Lower Thirds

- Lower Fourths

- Upper Seconds

- Models can be combined to form a new model.

Harmonic March Conditions

- Never forms a complete phrase, but must at least be member of a short phrase enough for successive transpositions, and must be symmetrical such that it is easily perceived by the senses.

- The sequence of the last chord of the model to the first transposed chord must not be a third order movement. Second order movements are allowed, but first order is preferred. Once the first transposition is completed, the harmonic march can be continued without worry of weak successions or bad degrees.

- Must end with a first(second?) order degree chord. Doing so by abandoning the perfect symmetry of a harmonic march for a satisfactory resolution is allowed, but is only practiced after regularly arranging the first chord of the last transposition.

- It must be designed so that it can be identically repeated in each transposition. It is sufficient to ensure the first chord of the first transposition is arranged in the same way as the first chord of the model, without realization mistakes. Forbidden melodic intervals are allowed, but only in transpositions, not the model.

The 7th Degree

- Its tonal effect is so small that it is only admissible as the result of a march.

- The 7th degree and the 2nd degree of the minor mode differ in their destination and their tonal effect.

- In the minor mode, every harmonic step to some extent contains a borrowed chord or a passing modulation. This is because of the 3rd and 7th degree of this mode, which are impractical, even in harmonic marches.

- Any second inversion must be on a first order degree and must be prepared and resolved by an oblique movement. For the other degrees, they can only be employed as a consequence of transpositions.

- Great use of harmonic marches is made in the fugue, but can apply to all styles. They acquire interest only by melodic artifices and dissonances.

The Sequence of Sixths – It can only be realized in four parts by imitation which converts the sequence into a harmonic march in either ascending/descending. They become more interesting through suspensions and other accidental notes (delays, anticipations, pedal).