Distant Keys are those outside of the conditions of relative keys (Ch 10.2). Two keys that are distant have fewer shared notes.

However, among the distant keys, there are several whose set of notes and chords shared with the main key is so great they may be called third class relative keys.

One key is the two modes with the same tonic, i.e. C major and C minor. Its obvious they two keys are closely related, especially because their shared dominant, which can be substituted for one another, isn’t a modulation, but a simple change of mode.

Furthermore, the main relative keys of C minor (E♭ major, B major, and F minor) each share several notes with C major, and modulations to these different keys (from C major) are soft and practiced frequently.

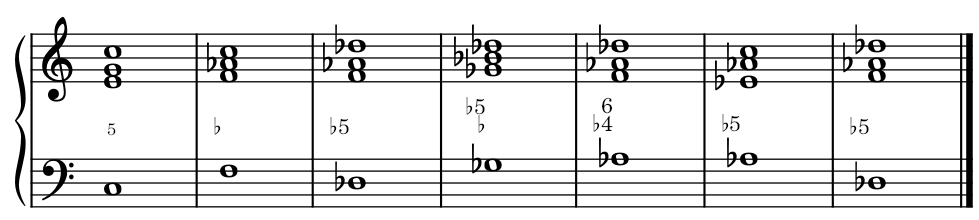

But as the number of common notes decreases, the modulations become harsher and more difficult to perform directly, so its better to use transitional chords to form passing modulations, each having some relationship with the key before it, and thus progressively serves to destroy the main tonal impression. Example:

(Modulation from C major to D♭ major.)

Use of the second inversion without preparation (Ch 7.3) is a powerful means, often abused, to impose a new, relative or distant key.

The duration of chords greatly influences the effect, good or bad, of modulations in general. A modulation with an excellent progression, can be shocking solely because its transitional chords are not long enough to prepare the new key.

Its crucial to be mindful when modulating to distant keys. Apart from the difficulties of realization and execution, they often weaken the tonal power of the piece. In the works of the great masters, they are only applied in long compositions, or when motivated by dramatic intention. Even still, there are few examples where distant keys are maintained for long periods.

Modulations to distant keys are mostly made using dissonant chords. However, this can also be done by consonant chords alone. The Basses to realize at the end of this chapter will prove it.