While second class relative keys contain more than one characteristic note (at least 2, at most 3), one of them is always the primary characteristic note and without it the modulation cannot be made.

The others are secondary characteristic notes, and chords containing them can only be transitional chords.

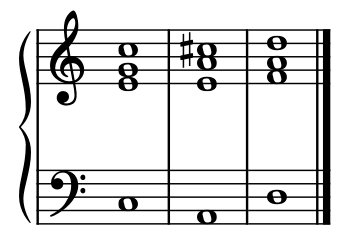

Thus, from C major to D minor, the primary characteristic note is C#, because the B♭ alone would lead to F major. Therefore, to make this modulation as direct as possible, use the dominant (5th) of D minor. Example:

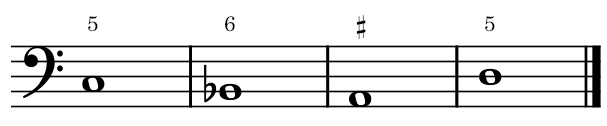

But any secondary characteristic note can, if it doesn’t determine the modulation, at least contributes by softening it, and varies its effects. Example:

In the previous example, the second chord serves as a transitional chord and acts as the subdominant (4th) of D minor.

(Make the complete table for each of the following modulations:

- C major to D minor

- C major to E minor

- A minor to G major

- A minor to F major

- A minor to E minor

- A minor to D minor

For each of these modulations, only use the primary characteristic note first, which is generally the leading tone, except in the modulation from A minor to F major.

Repeat the same tables by introducing all the characteristic notes through the transitional chords that contain them, in each of the second class relative keys.

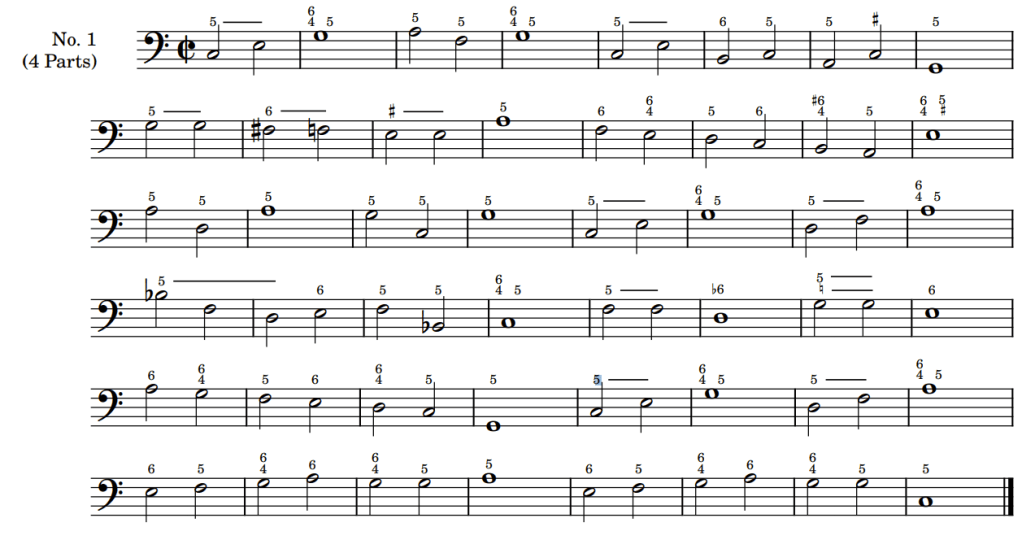

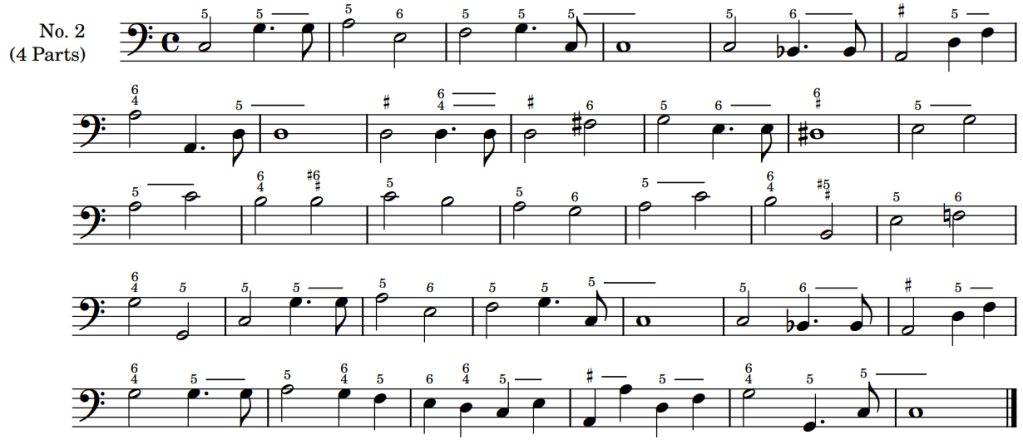

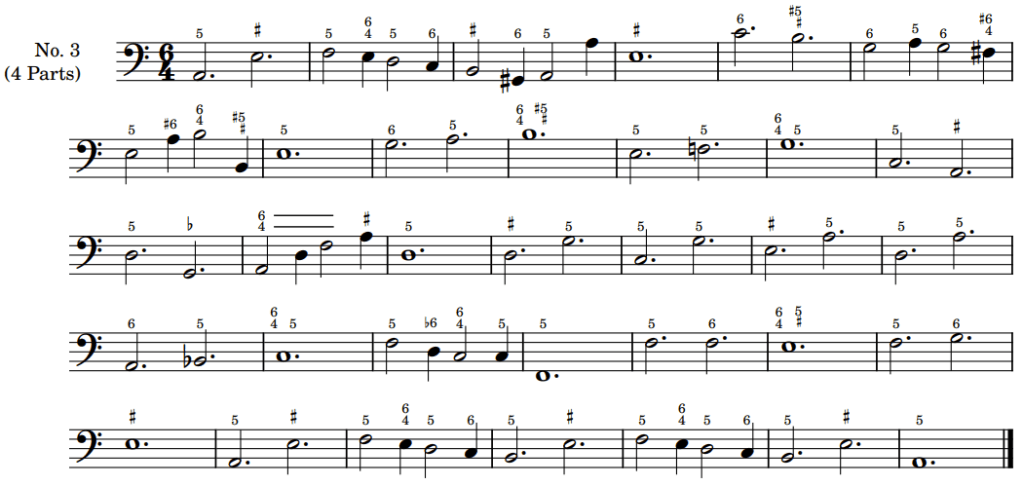

Basses to realize

Reflections

Among the laws which establish a piece’s unity and clarity, one of the most important is the one which recommends a main key. The main key of the piece is usually imposed by the starting phrase. Once the key is established, the musical feeling is settled and doesn’t willingly accept premature modulations that could replace the initial tonal impression.

Also, the shorter the piece, the less you have to deviate from the main key. But as a piece grows longer, staying in the same key inevitably leads to monotony. Thus, modulations become necessary for variety. They must present themselves as episodes relating to a set, and if the piece is long, the main key must reappear sometimes and occasionally, so that its impression isn’t lost.

Finally, the ending phrase of a piece can only be in the main key.

Tonal modulation between keys which share many common notes, and common chords, are evidently the most natural, gentlest and cause the least disturbance to the main key.

Therefore, in all works worth mentioning, modulations to relative keys are much more frequent than those to distant keys. Composers before the second half of the eighteenth century offer very few examples aside from the relative keys of the main key of a piece. Even today, this same relation of keys is required in schools for the work of counterpoint and fugue. This requirement is very salutary. Artists whose talent is matured by experience can appreciate how much a modulation can have a good or bad effect on the whole piece, and how important it is to subordinate everything to the main key.