First, we’ll deal with the simplest and most direct methods of modulating. Abstractly, this is the place of the chords in the phrases, the arrangement of their notes, their duration and the influence of cadences.

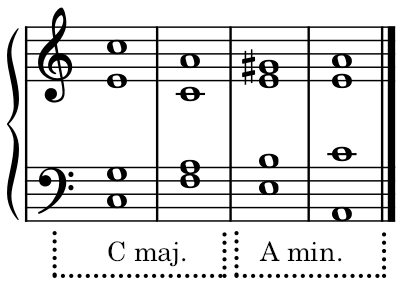

To modulate to any first class relative keys, its enough to choose a chord which contains the characteristic note (Ch. 10) in the destination key. As soon as this chord is heard, the new key is addressed. Example:

Its essential to establish laws pertaining to which two chords of different keys can be linked together.

Rule: Any degree of the first key can be linked together with all the degrees of the new key which contain the characteristic note, except the 7th degree in the major and minor mode. This progression must be satisfactorily realized and must not break the various rules regarding performance.

In short, one can leave on any degree of the first key except the 7th, and arrive at any degree of the new key except the 7th.

Exception: this doesn’t apply to harmonic marches (Ch. 11) because in certain cases, we can leave the key on the 7th degree.

Note: Even though the role of the mediant (3rd) of the major mode is very limited, especially in modulations, and its use has few examples because of the numerous cases where its effect is bad, it hasn’t been excluded here from the chord which can contribute to modulations, because in many cases it could be used to produce new effects.

Exercises

- Modulate in a major key to its 3 first class relative keys.

- Modulate from a minor key to its first class relative key.

You can use very short chord progressions wherein you may assume the start key has already been established. You will take care to place among the first chords of each modulation a chord which restores the main key by destroying the characteristic note of the previous modulation. You will have formed a table of modulations. Play these modulations on a piano, generally in four parts, sometimes in three, depending on what suits the exercise the best. This table should contain as many combinations as possible, except the ones with a bad effect. The following guidelines will guide this work.

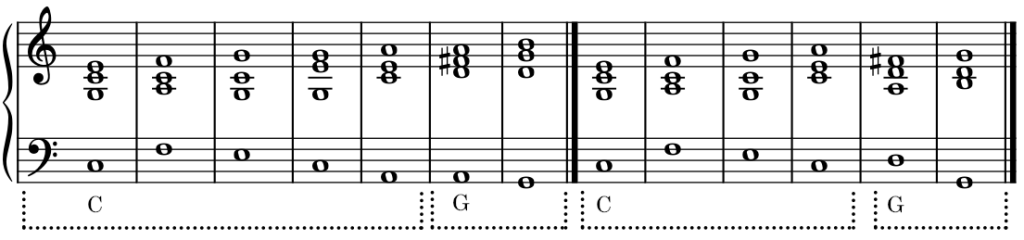

Modulation to the Fifth Above

(C major to G major)

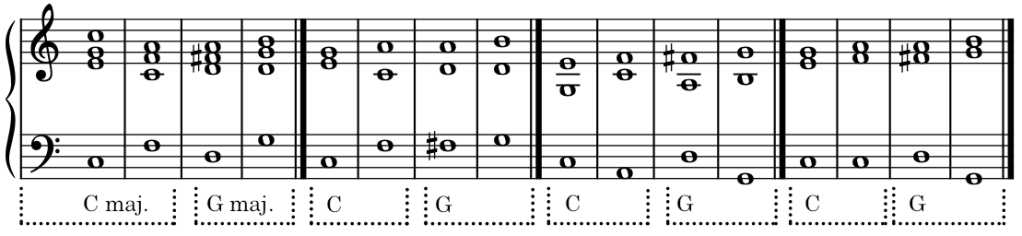

The characteristic note of the key of G major relative to C major is F#, which is part of the dominant (5th) and the mediant (3rd) chords of G major (As for the 7th degree, its understood that its job is null.)

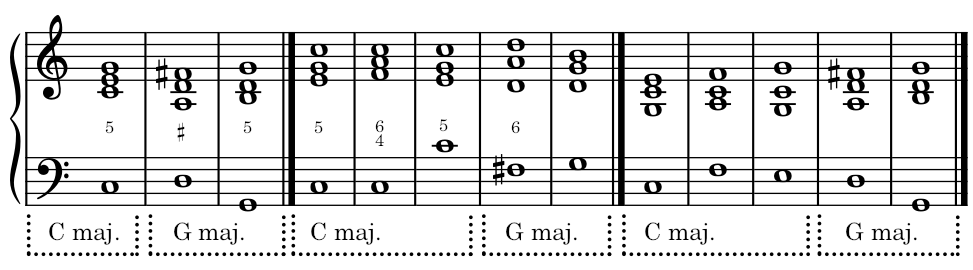

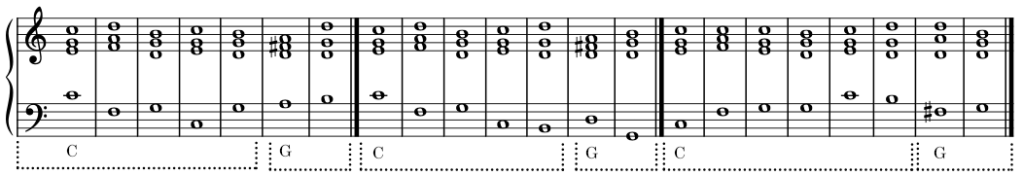

Examples Using the Fifth Degree of G Major

1. Leave C major on the tonic and its inversions, enter the key of G major by its dominant (5th) and its inversions. (Remember, for every second inversion except the tonic, the fourth must be prepared and resolved.)

2. Leave C major on the supertonic (2nd) and its inversion, enter the key of G major by its dominant (5th) and its inversions.

3. Leave C major on the mediant (3rd) and its inversion, enter the key of G major by its dominant (5th) and its inversions.

4. Leave C major on the subdominant (4th) and its inversion, enter the key of G major by its dominant (5th) and its inversions.

5. Leave C major on the dominant (5th) and its inversion, enter the key of G major by its dominant (5th) and its inversions.

6. Leave C major on the submediant (6th) and its inversion, enter the key of G major by its dominant (5th) and its inversions.

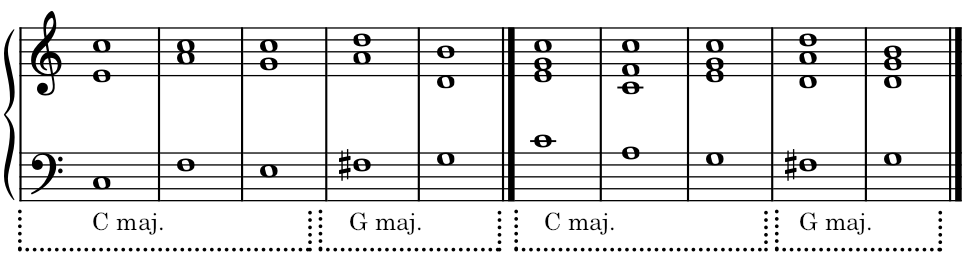

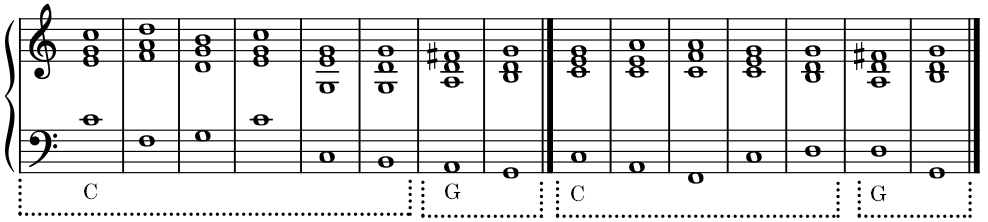

Examples Using the Third Degree of G Major

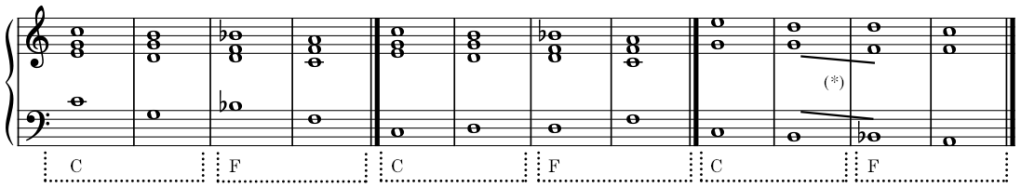

In the modulation from C major to G major (or in any modulation to the fifth) the third degree, having a weak tonal influence, offers little influence as a characteristic chord. Nevertheless, is some very rare cases, it can be used. Example:

especially when its to strengthen the new key by means of its 5th degree. Examples:

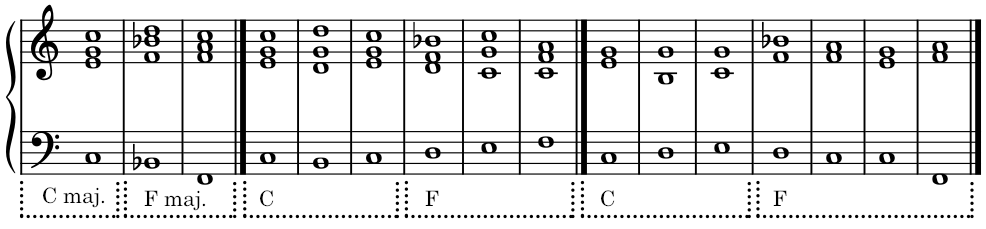

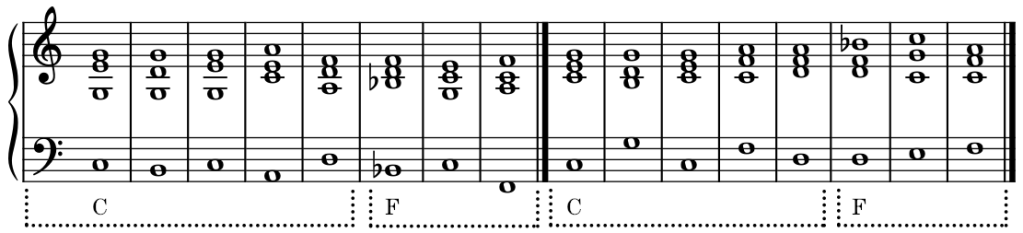

Modulation to the Fifth Below

(C Major to F Major)

The characteristic note of F major relative to C major is B♭, which is part of the subdominant (4th) and the supertonic (2nd) of F major.

This modulation often gives rise to the tritone relation (B♭ and E), and some modulations are harsh and rejected.

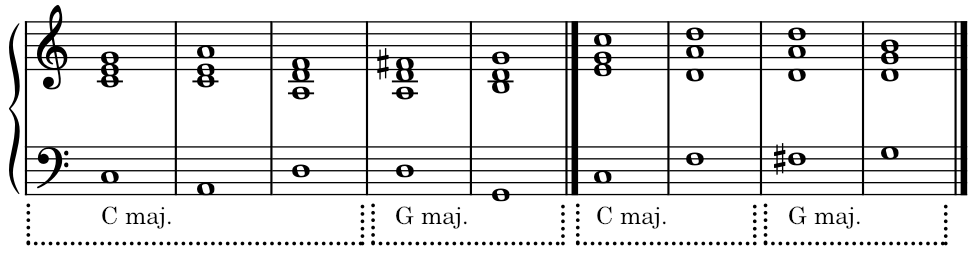

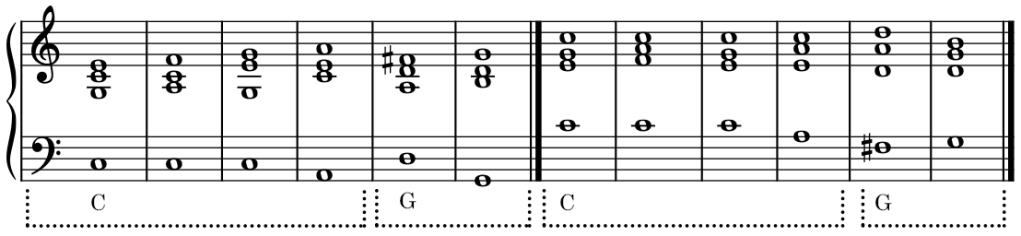

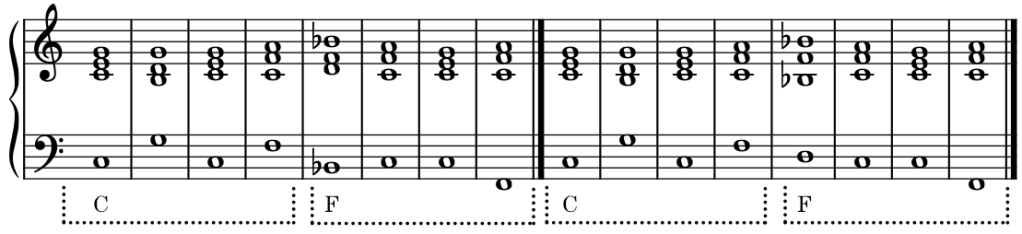

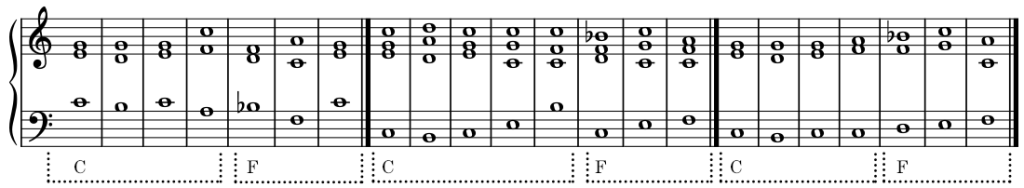

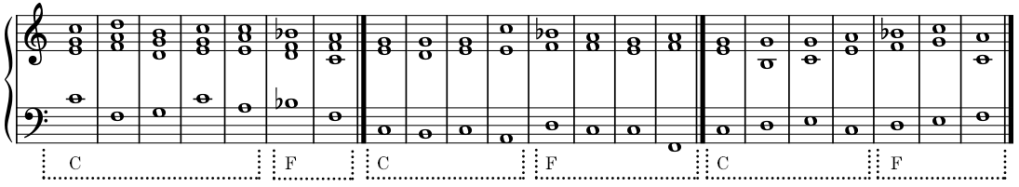

Examples Using the Fourth Degree of F Major

1. Leave C major on the tonic and its inversions, enter the key of F major by its subdominant (4th) and its inversions.

2. Leave C major on the supertonic (2nd) and its inversions, enter the key of F major by its subdominant (4th) and its inversions.

3. Leave C major on the mediant (3rd) and its inversions, enter the key of F major by its subdominant (4th) and its inversions. This progression has an extremely harsh effect. The next one is more admissible.

4. Leave C major on the subdominant (4th) and its inversions, enter the key of F major by its subdominant (4th) and its inversions.

5. Leave C major on the dominant (5th) and its inversions, enter the key of F major by its subdominant (4th) and its inversions.

* Regarding the perfect fifths, see Supplementary Chapter article 2.

6. Leave C major on the submediant (6th) and its inversions, enter the key of F major by its subdominant (4th) and its inversions.

Using the Fourth Degree of F Major

(The student will make this table themself.)

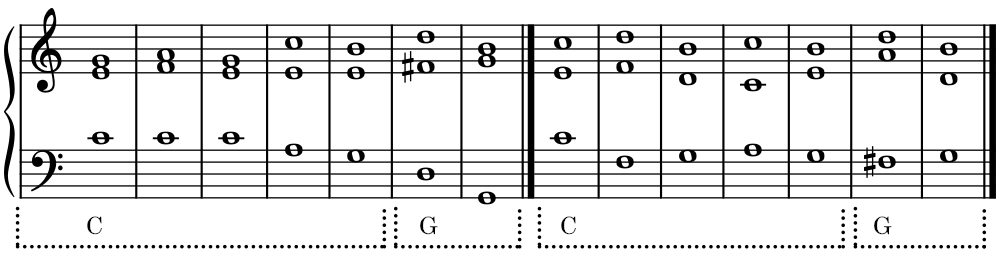

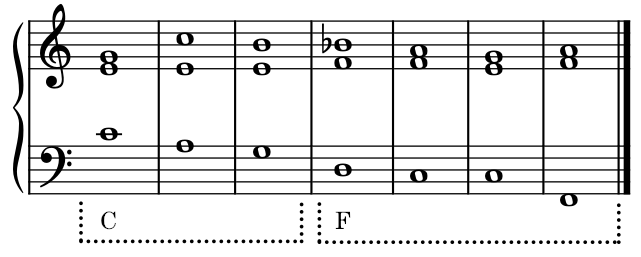

Modulation to the Relative Minor

(C Major to A minor)

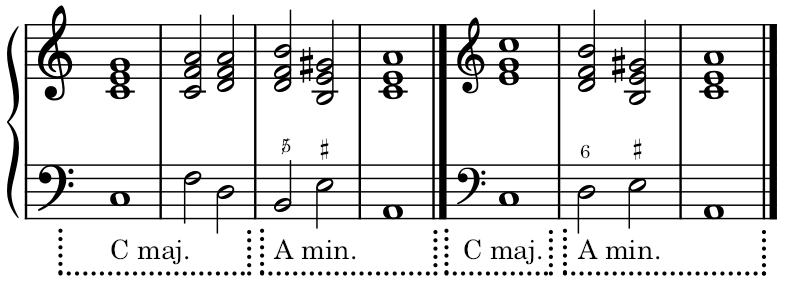

The characteristic note is G#, and the modulation can only be decided by the dominant (5th) of A minor. Example:

(Complete the table of this modulation.)

Note: Although the G# (leading tone) is essential to make this modulation, the diminished chord of the 2nd degree, particularly distinctive of the minor mode, makes sense and can be used, an otherwise characteristic chord, as a lesser transitional chord:

In the two previous examples, its necessary to consider the chord B, D, F, as the 2nd degree of A minor and not as the 7th degree of C major. For now, accept this as fact. The true effect of the leading tone (7th) will only be appreciated in the chapter on Harmonic Marches. Outside of harmonic marches, the chord of the leading tone (7th) has not satisfactory application.

Modulation to the Relative Major

(A Minor to C Major)

The characteristic note is G natural, which is part of the tonic (1st), mediant (3rd), and dominant (5th) of C major. These chords can be used to modulate, but the dominant (5th) is the best. (Make the tables.)

From the modulation tables to be made by the student, its important to be convinced the effect of a modulation is quite different based on the chord we leave the first tone and the chord we enter on the new tone. Its from this principle that variety and surprise are born in the art of modulation.

When making the modulation tables, make them similar to the given examples. We don’t intend to imply the secret to finding beautiful modulations is by meticulously writing out every possible modulation. The intention of the modulation table exercises is to quickly accustom the student to the all the resources available for modulation. Too frequent use of a few formulas restricts talent and deflowers even great works. Fertilizing the mind and memory also develops the imagination.

In reality, these tables only offer raw resources which the student will apply later to different phrases, rhythms, and formulas. The relative duration of a chord, its place in a phrase/measure, and how its realized, all affect the modulations. The dissonant chords and melodic notes enriches the modulation. Finally, certain passing notes often make the parts more singable, and thus, making the modulations more natural and harmonious.

Regardless of the method taught for modulations, the important conclusions is this:

the chords of the good degrees are preferably chosen, either to leave the first tone, or to enter the new tone. But the chords of the second even the third order mustn’t be excluded and can be used in modulations.