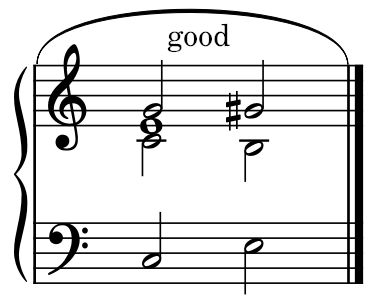

Rule #1: Any chromatic change must be made by one part. Example:

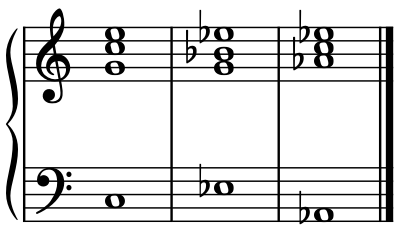

Breaking this rule often results in the bad effect of a false relation. Example:

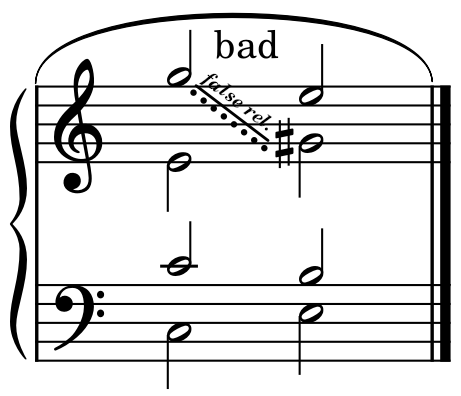

Note: the term false relation of the octave is commonly used. This example:

is enough to prove this term is illogical, as there’s no octave interval from the G to the G# here.

Sometimes the bad effect of certain false relations is reduced by certain chord positions and by the importance of other parts. This is especially true when the false relation takes place between an intermediate part and the Bass, and lands on the characteristic note (9.1).

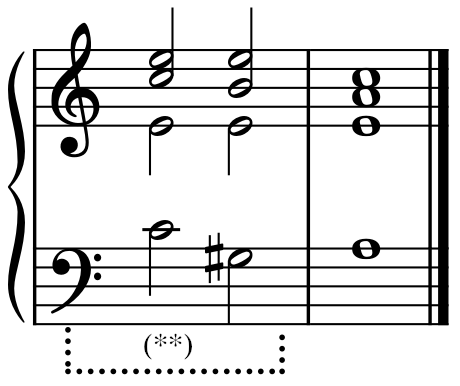

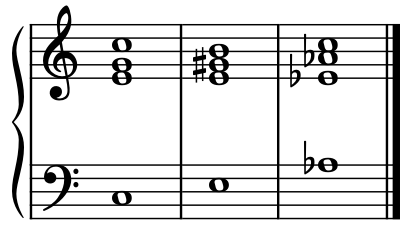

Thus, the realization of this example:

is often used in the free style, but must be avoided in school/study. The previous examples must be realized as follows:

(**) Regarding the diminished fourth, see 2.6.

In summary, the student mustn’t allow any false relation. Experience and taste alone can be judged by the small number of those eligible.

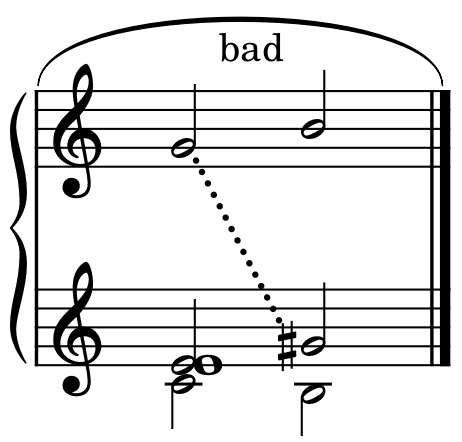

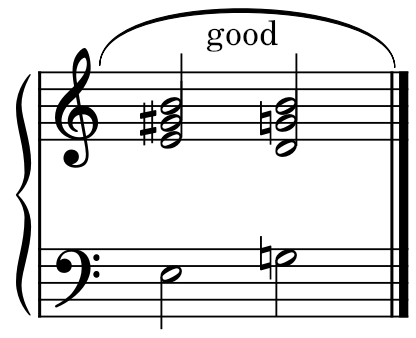

Exception: The harmonic version of the following example:

must be permitted as having a very good effect, thought it also contains a kind of false relation, but is in fact, not complete, since one of the parts performs a chromatic change.

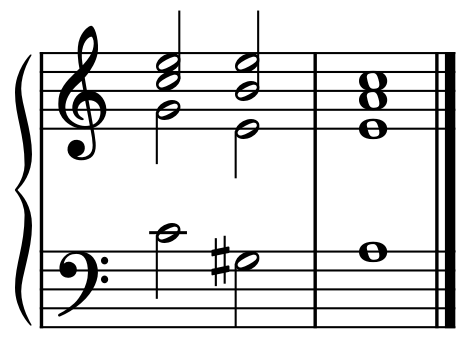

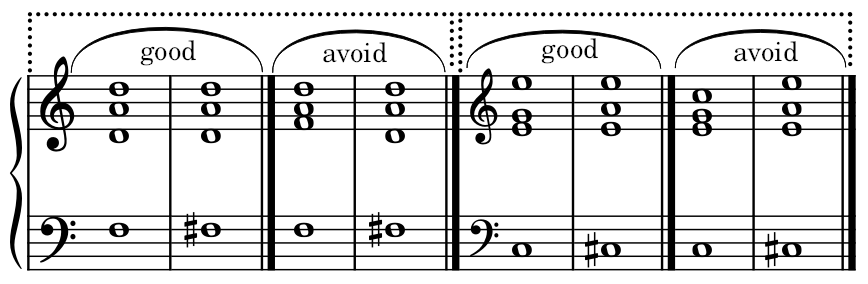

Rule #2: Avoid doubling the note that will undergo a chromatic change whenever possible. Examples:

Rule #3: Any leading tone determining a modulation must go to the tonic note, in both the major and minor mode.

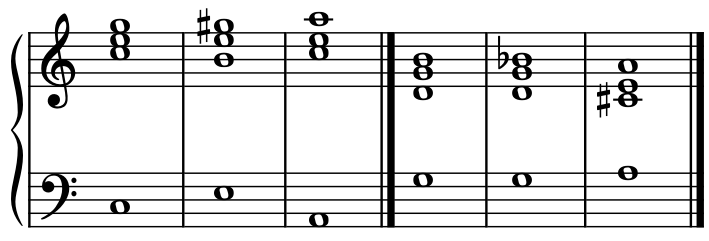

Rule #4: Any note resulting from a chromatic change, must move to the adjacent note above if the chromatic change is ascending, or to the adjacent note below if the chromatic change is descending. Examples:

It can also remain motionless. Example:

Or change enharmonically, which is rare. Example:

Exception: in cases similar to the following:

This rule doesn’t apply because one of the parts (in this case, the intermediate part) is difficult for intonation, or is hard to sing. Its best to realize it these ways, where the latter is better:

Note: the melody of the parts, important to the beauty of any musical composition, is especially important in modulations. It can be said, in general, when one or more parts perform melodic intervals of difficult intonation (2.6), the modulation has a bad effect.