The following paragraphs define the properties and the general character of suspensions.

The preparation must be at least as long as the suspension. In other words, its necessary to avoid the limp bond (CH. 13.1) from the preparation to the suspension.

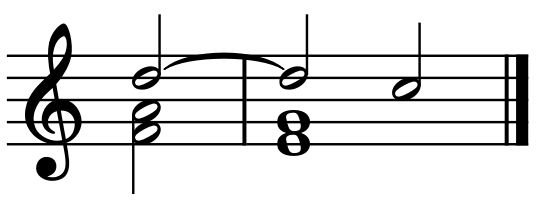

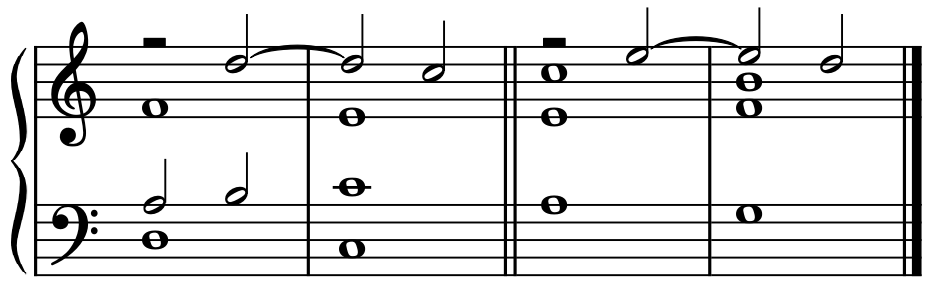

The suspension or suspended note must land on a strong beat. Example:

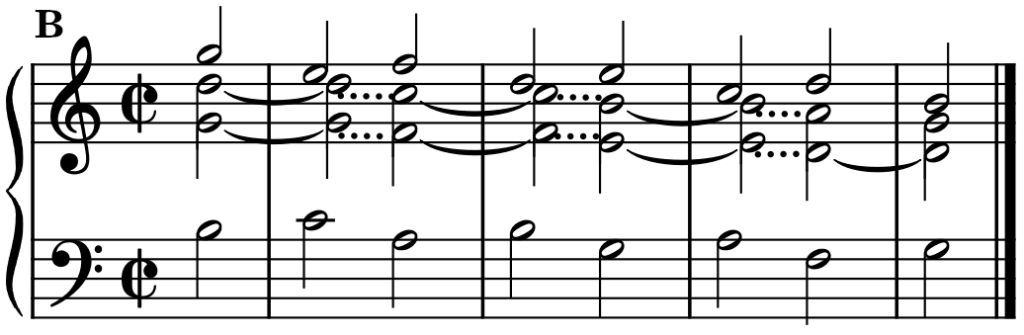

However, every beat of a measure can hold a suspension on the strong part of its beat, especially in slow or moderate tempos. Example:

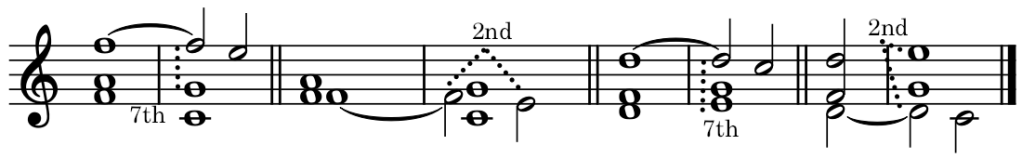

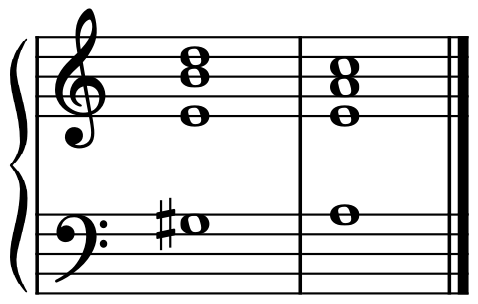

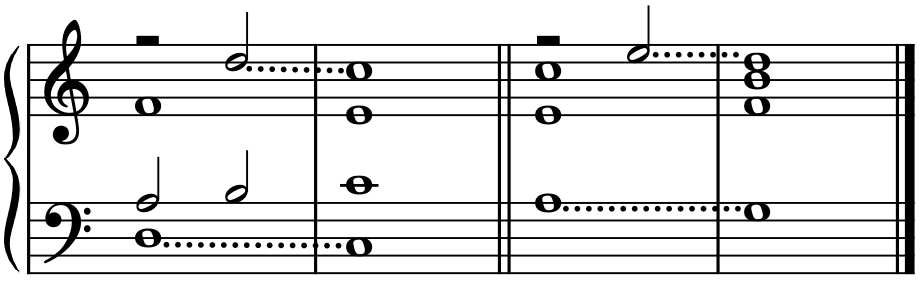

The suspension must result in a dissonance, either seventh or second, with one of the real notes of the chord. Examples:

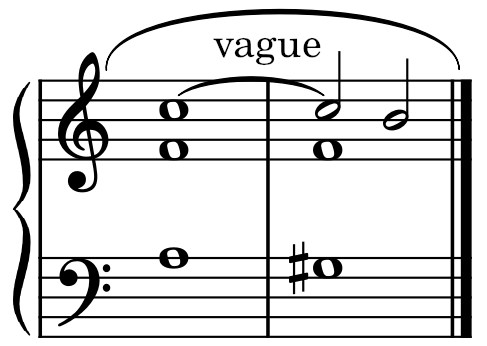

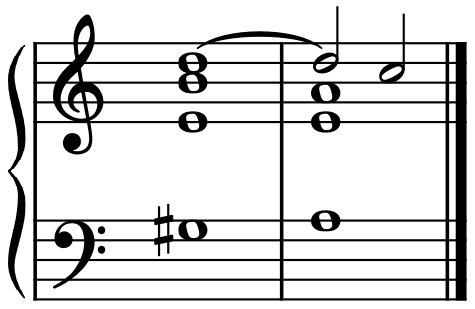

Aside from other dissonances which may be part of the chord, any suspension which isn’t a second or seventh dissonance is generally avoided due to its vague effect. Examples:

In general, a suspension may occur in any part and within any inversion. However, the restrictions in CH 20.2. and CH. 20.3 apply.

The duration of the suspension is arbitrary. Its subject to instinct and taste. Generally, it rarely lasts a whole measure of an adagio movement.

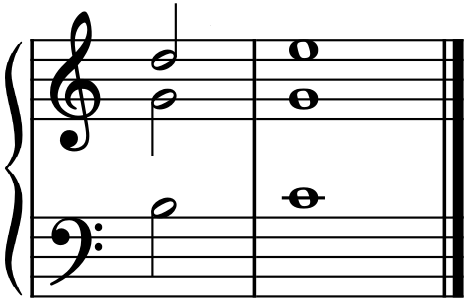

The suspension temporarily occupies the place of the delayed note which is an adjacent note below. In other words, the suspension represents the adjacent note below. In this case, the suspension is above. Examples:

Same harmony without suspension:

by extension and by analogy, a delay occupying a strong beat and represents the adjacent note above, is also called a suspension. In the case, the suspension is below. Examples:

Same harmony without suspension:

We see from these examples that every suspension makes it natural resolution to the delayed note it replaces. Thus, the Suspension Above resolves by descending one degree. This is why its called a descending suspension. The Suspension Below resolves by ascending one degree. This is why its called an ascending suspension.

In general, suspensions resolve on a weak beat, or a beat less intense than the one occupied by the suspension, unless its lasts the whole measure.

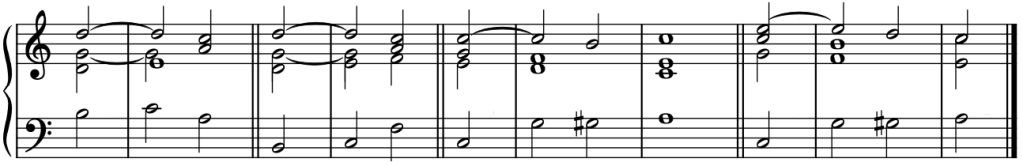

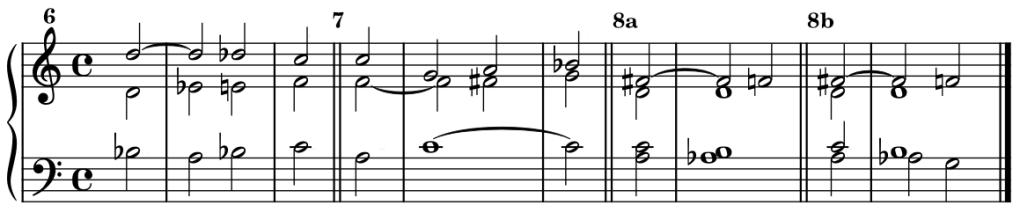

The chord may change when the suspension resolves, as long as the resolution note is a real note of the new chord. Examples:

When the suspension resolves, no other part may resolve to the same note nor an octave of this not by direct motion. This is in line with CH. 13.1 Rule 3 on the resolution of dissonant notes. Examples:

Conditions for Using Suspensions

To ensure a suspension is passable, its subject to the following two events:

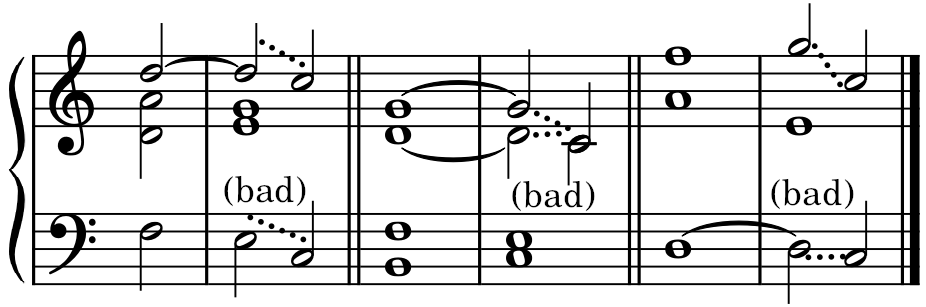

Condition #1: If the suspension were substituted with the note it represents, the harmony must be correct (BOOK II). Thus, the two following examples:

Are bad, because by reducing them to their real notes, we get:

Which are consecutive octaves in the first example, and consecutive fifths in the second example. These may be called hidden fifths and octaves (see note in CH 2.6), implied, or more generally, delayed. However, this latter term may cause them to be confused with those in CH. 5.2, which are not the same as the examples above.

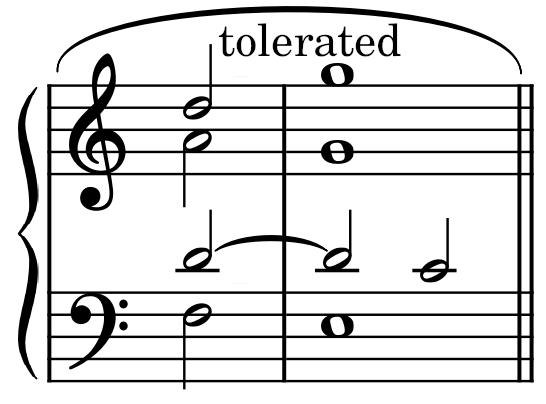

Note: However, implied fifths are tolerated when formed by an inner part and the upper part with the suspension placed on the inner part. Example:

Or when the suspension is formed by two inner parts, and the Bass reduces its harshness (CH 7.1).

Condition #2: The resolution note mustn’t produce a fault in harmony with the notes simultaneous struck with it.

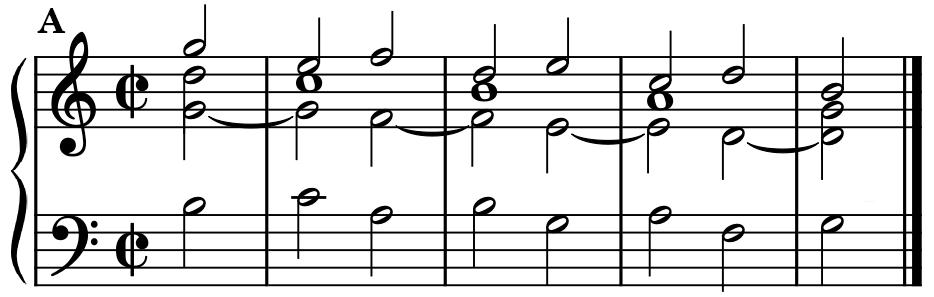

Thus, the harmony of Ex. A is correct, but the introduction of suspensions in Ex. B make it faulty (consecutive fifths).

Exceptional Resolutions of Suspensions

Resolution #1: Like any dissonance, the suspension can remain in place to form a real part of the next chord.

Resolution #2: The suspension can be resolved by changing chromatically. This case is very rare.

Notes to Delay by Suspension

It’s obvious we can only suspend the notes of a chord which do not require preparation. The sixth and seventh notes of the minor mode cannot suspend each other, as they these two notes always form an augmented second.

Classification of Suspensions

Classification #1: Simple when only one chord note is suspended.

Classification #2: Simultaneous when two, three, four notes of a chord are suspended at the same time.

Simple suspensions are infinitely more numerous and more used than others, which is why this work shall deal with simple suspensions first in 20.2 an 20.3.

Suspension Figurations

The same principle for real notes applies to suspensions. That is, its expressed in figures with the most important upper notes intervals formed with the bass. But this is often ambiguous and results in confusing combinations of figures which don’t make it possible to guess the nature of the chord based on the position of the notes. There are quite a number of chords with suspensions which need all intervals written, as its impossible to quantify them clearly. These chords, in the following articles, are unfigured.